Note: While the political machinations discussed below may prove scandalous to some readers, it should be remembered that the divinely ordained Kingdom of Israel experienced comparable political battles and ultimately schismed into two separate kingdoms as a result. Consequently, it is the author’s contention that the squabbles outlined below, as well as the subsequent Great Schism between East and West, actually serve to underscore that the Church is in fact the fulfillment of the Old Israel and indeed established by Christ.

Each year I make a single New Year’s resolution so that it is more effective and feasible than juggling a laundry list of various resolutions. In 2022, my goal was to read all of the translated Acts of the first millennium Ecumenical Councils, as well as of any significant synods that occurred within that time period. I began in March, and 5,000+ pages later, I have accomplished my mission of sufficiently exhausting the translated works of the United Church of Christendom right before the New Year. The main resources I have utilized in this endeavor have been Fr. Richard Price’s translations, as well Catholic Historian Francis Dvornik’s work on the Photian Schism. Along the way, I summarized the Acts and events of the Councils, focusing on the competing ecclesiologies of the East and West, which I will provide below for the reader’s edification. Unfortunately, we are not in possession of the Acts of the First and Second Ecumenical Councils, and consequently, I have not created a summary of those important councils. In retrospect, this was an oversight on my part, as I could have still summarized the research I completed on these councils with the resources I did have at my disposal – perhaps, this can be accomplished in the future. The content I provide below has not been thoroughly reviewed and should not be considered a completed work, but hopefully it may serve as a helpful introduction to the topic, as well as a launchpad for a greater project down the road. A chart providing a brief timeline of the councils and events is also provided at the end of the post. Of particular note, the Photian Schism is a series of events, or a collection of synods, that occurred towards the end of the first millennium and facilitated arguably the greatest tragedy the human race has experienced in the Christian Era: the Great Schism between East and West which has persisted to the modern day. May God have mercy on his Church. Without further ado:

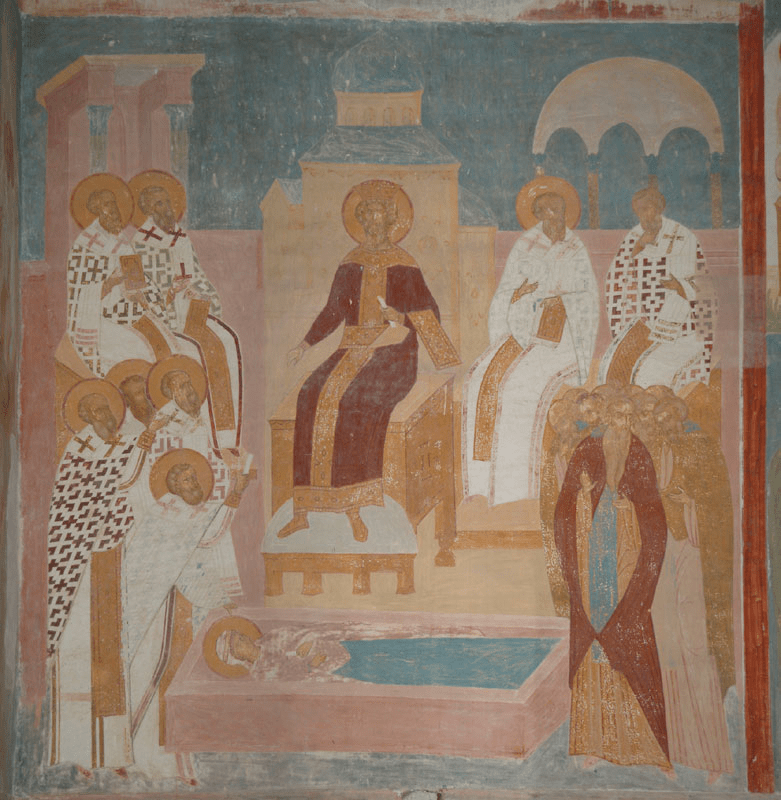

• The 3rd Ecumenical Council •

• The Council of Ephesus of 431 •

A controversy over Cyril of Alexandria’s Christology began to shake the Empire, as the debate had been ignited principally by Cyril’s use of the term “Theotokos” (God-bearer) in reference to Mary. Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, objected to Cyril’s emphasis on Christ being the same subject as the Word of the Trinity and consequently this one Divine Person being the subject of the experiences of Christ’s human nature. Similarly, the Antiochenes were also concerned that Cyril had made God passible in proposing that the Second Person of the Trinity experienced human realities through the human nature of his incarnation. Instead, Nestorius proposed that a second person, distinct from but united to the Second Person of the Trinity, was the subject of the human experiences of the incarnation. Nestorius and the Antiochenes’ theological failure lay in their inability to properly distinguish between the categories of person and nature. In response, Pope Celestine called his own local council in Rome in 430 to address the dispute, at which he affirmed the Cyrillian view. However, the rest of Christendom did not consider the issue definitively settled and as a result the Eastern Emperor Theodosius II convened a council at Ephesus in 431 to put the matter to rest. Subsequently, Rome dispatched Cyril to implement their own Christological decisions at the ecumenical council. The Council of Ephesus promptly split into two camps due to Cyril’s questionable conduct, as he violated imperial orders by refusing to wait until the arrival of his opponents before proceeding with the council, and instead, immediately excommunicated them in their absence. Once they finally arrived, the Antiochenes and Nestorian supporters did the exact same to Cyril in response. The ensuing initiatives of the competing assemblies consisted of producing a series of letters to the Emperor, attempting to persuade him of their respective views. Notably, the Emperor was repeatedly referred to as head of the Church by the council attendees; conversely, none of the bishops focused on convincing the Pope of their position. Yet, it would be disingenuous to pretend the Pope’s support on the Christological controversy lacked significant weight in conciliar discussion. When Pope Celestine’s legates arrived at the council, they invoked their succession to Peter as being near-assurance of their orthodoxy and indicative of their responsibility to take care of all the churches. While no other bishops objected to these claims, at the same time no other bishops in Cyril’s camp used these claims as definitive proof of the orthodoxy of their Christological position that was being backed by Rome. Cyril’s Christology ultimately won the propaganda war based primarily on the size advantage of his party (250+ bishops vs. Nestorius’ ~30) and as a result of his paying off the Imperial Court with gold and valuables from his churches in Alexandria.

• The 4th Ecumenical Council •

• The Council of Chalcedon of 451 •

As an over-extrapolation of Cyril of Alexandria’s Christology as dogmatized at the Council of Ephesus in 431, bishops began to postulate that not only was Christ one Person but that he also maintained one nature after the incarnation. Cyril’s successor at Alexandria, Dioscorus, was the main proponent of this Christology, in tandem with a prominent bishop in Constantinople named Eutyches. They were concerned that a Christology proposing two natures would be a continuation of the Nestorian heresy which implied two persons, and consequently they condemned the rival dyophysite position at the robber council of Ephesus II in 449. However, Pope Leo, Flavian of Constantinople, and other eastern bishops were opposed to both the doctrinal decisions and the management of this council, putting pressure on Emperor Marcian to call a new council in order to remedy the growing debacle. Consequently, the Council of Chalcedon was held in 451 and condemned both Dioscorus and Eutyches for their non-canonical conduct at the robber council in 449, as well as for their heresy of monophysitism. Ultimately, the Council affirmed and ratified the orthodoxy of Leo’s strict position of two natures existing after the incarnation as detailed in his Tome. Pope Leo himself had viewed this Tome as sufficient in itself to address the issue, while the rest of the council considered it necessary to assess the Tome’s orthodoxy and to ensure it aligned with the Christology of both Cyril and the Council of Nicaea. While legates of the Pope continued to stress his role as head of the Church and successor of Peter, the council referred to the Emperor as the “divine head,” focusing on the consensus of the Church and Imperial ratification as the basis for the validity of the council. In fact, much to Pope Leo’s chagrin, the canons of the council elevated Constantinople to the rank of second See, above the Petrine Sees of Alexandria and Antioch, and allowed appeals to be submitted to the See of Constantinople in Eastern disputes.

• The 5th Ecumenical Council •

• The Council of Constantinople II of 553 •

The main purpose of this council was to enshrine Emperor Justinian’s condemnation of the Three Chapters. The Three Chapters were Nestorian writings opposed to the Orthodox Christology that had developed through the councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon. Chalcedon had reinstated authors of the Three Chapters to their episcopates – contributing to the Non-Chalcedonian concern that Chalcedon had simply been a revival of Nestorianism. In a failed attempt to reunite Non-Chalcedonians and Chalcedonians, Justinian condemned the Nestorian Three Chapters and at least one of its deceased authors. Pope Vigilius objected to the idea of posthumously anathematizing individuals, let alone those who had also been reinstated by a prior council, as well as going beyond what Chalcedon had already decided by condemning the Three Chapters. Vigilius ultimately waffled on his position and bound the universal Church to two contradictory positions throughout the saga: at first, forbidding the condemnation of the Chapters, and then eventually mandating their condemnation in the end. The Emperor and council attendees did not view Papal commands as intrinsically binding – although Vigilius considered himself above the council – as the council explicitly stipulated that Vigilius needed to work within a conciliator context for his decisions to be valid. Indeed, the bishops of the council explicitly stated that an individual should not presume to represent the consensus of the Church by himself before the entirety of the Church is heard at council. Ultimately, Constantinople II deposed Vigilius as a heretic and struck him from the diptychs for initially refusing to condemn the Chapters; in fact, the Emperor even had him imprisoned. Interestingly, the council still considered itself in communion with the Roman Church as a whole but simply understood the Roman See to be vacant. Constantinople II proceeded onwards without the Pope, officially condemning the Three Chapters and anathematizing a deceased author of the Chapters. Vigilius died before he could return to Rome, but he had eventually assented to the council’s condemnation of the Chapters and Constantinople II was in the end accepted as ecumenical by the Western Church. Ironically, despite its bouts with the papacy, the failure of the council to garner a significant number of attendees contributed to the growing notion that it was essentially Imperial and Papal confirmation which conferred ecumenicity on a synod.

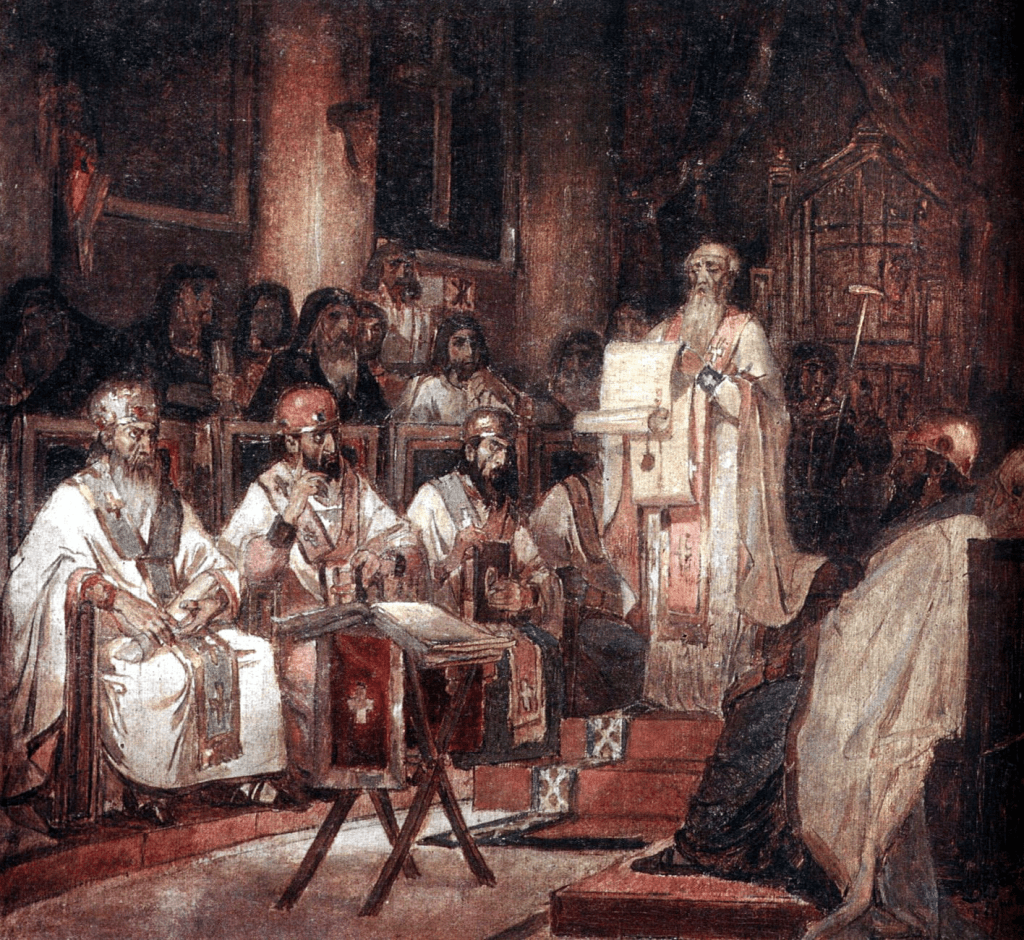

• The Lateran Synod of 649 •

• Western Synod •

In response to the growing monothelitism and monoenergism in the East, St. Maximus the Confessor collaborated with Pope Theodore in the West to convoke a council in Rome regarding the controversy. Pope Theodore passed away before the council could officially convene and Pope Martin ascended to the pontificate in his place. The Lateran Synod was ultimately attended primarily by bishops of the West, mainly from Italy, with a small contingent of Greek monks in order to keep up appearances that the council maintained some sort of ecumenical representation. However, the Lateran Synod itself never gained the status of an Ecumenical Council either in the West or the East, despite its papal ratification and St. Maximus’ belief that it was ecumenically binding. The Synod essentially implemented Maximus’ position on the two wills and energies of Christ, while also condemning the Typos and Ekthesis declarations for their toleration of monothelitism and monoenergism. It was a pivotal movement in papal development as it was the first time that the bishop of Rome had attempted to convoke a council with the intent of being ecumenical, for this had always been the prerogative of the Emperor. Likewise, the Acts of the Lateran Synod are full of examples of Pope Martin claiming for the papacy unique Petrine authority to universally shepherd Christ’s flock, deriving from Peter having singularly received the keys. The decisions of the Lateran Synod regarding the two energies and two wills of Christ would be echoed in the doctrinal definitions of the Sixth Ecumenical Council just a few decades later in 681.

• The 6th Ecumenical Council •

• The Council of Constantinople III of 681 •

An English translation of the acts of this council unfortunately does not currently exist. However, OrthoWiki, New Advent, and historian Edward Siecienski have provided translations and summaries of various noteworthy aspects of the council. The council was convoked by Emperor Constantine IV to settle the monothelitist and monoenergist disputes that were continuing to rage in the East. Pope Agatho wrote a letter to the council communicating the West’s dyothelite and dyoenergist position, while emphatically stressing his full-blown Petrine prerogatives. Agatho went so far as to indicate that the Roman Church is the rock of the universal Church and will be guarded from error by Peter for all eternity. The council itself appears to have received the letter’s contents as “suggestions” and examined them for orthodoxy before granting the letter approval. In striking irony, the council also posthumously anathematized Pope Honorius for what they described as a participation in the monothelitism of the heretic Sergius – and the papal legates did not object. Ultimately, the letter of Pope Agatho was accepted and ratified by the council, which virtually enshrined the Christology of St. Maximus and Pope Martin as previously delineated at the Lateran Synod of 649. However, for political reasons, the council refrained from making any explicit nods to either St. Maximus or Pope Martin.

• The Quinisext Council •

• The Council of Trullo of 691 – 692 •

Justinian II convoked this council with the intent of establishing disciplinary canons to supplement the Fifth and Sixth Ecumenical Councils since they had failed to distribute canons themselves. The Quinisext Council from the onset claimed for itself ecumenical status but interestingly was never listed as a separate ecumenical council in the East or West. Moreover, while Rome was invited to the council and was sent its canonical decisions, Rome declined to attend or to ratify the synod as it confronted no major doctrinal matter and issued two canons directly opposed to Western disciplinary practice. Ultimately, the Quinisext Council was received in the East as the completion of the Sixth Ecumenical Council, while the West tended to view it as merely Eastern disciplinary law not binding on the West due to its lack of Papal ratification. The Quinisext Council demonstrated the continued growth of Imperial prerogatives, as the synod advanced the notion that the Emperor was the fulfillment of the Old Testament kings of Judah and codified his right to enter the sanctuary to incense the altar and offer gifts. Likewise, while the Emperor had first signed onto a council’s proceedings only at the Sixth Ecumenical Council and even then had been listed subsequent to all the attending bishops, at the Quinisext Council the Emperor’s signature appeared first on the list. Of note, the Quinisext Council condemned the consumption of blood, the depicting of Christ as a lamb, and laws forbidding priests to partake in marital relations. Moreover, it reinforced the privileges of Constantinople to settle Eastern disputes as previously canonized at Chalcedon.

• The 7th Ecumenical Council •

• The Council of Nicaea II of 787 •

In 754, in the midst of an iconoclastic empire, the Council of Hiereia was held in order to condemn the veneration of images and it declared itself the seventh ecumenical council. However, 33 years later, with a change in imperial dispositions, the Council of Nicaea II was convened by Patriarch Tarasios of Constantinople at the behest of the Emperor and Empress in order to revoke the decisions of Hiereia. Nicaea II delegitimized the conclusions of Hiereia based on its failing to garner the ratification of all the Patriarchs, as the Pope and the Oriental Patriarchs never confirmed the council. In Nicaea II’s official Refutation of Hiereia it declared that an Ecumenical Council must receive Papal cooperation, the assent of all Patriarchates, and be in accordance with the teaching of the previous Ecumenical Councils. Contrastingly, Pope Hadrian I wrote to Nicaea II that it is his role to guard the faith as the unique successor to Peter, that Peter will have a successor in his See until the end of time, and he seemed to imply his ratification is singularly that which grants a council binding authority. Similarly, when inviting the Pope to the council, the Emperor and Empress acknowledged him as uniquely the head of the Church – yet they stressed that the doctrinal dispute should be resolved synodically so as to avoid schism. Ultimately, Nicaea II defended the veneration of images based on its purported apostolic origins and the rationale that the veneration passes beyond the image to the prototype. The council itself and the East promptly considered Nicaea II as ecumenical, however, Rome only officially accepted it as the Seventh Ecumenical Council during the Photian dispute of the 9th century essentially as a quid pro quo. Of note as well at the council: Patriarch Tarasios confessed a type of Filioque in the Creed (“through the Son”), the council demonstrated a full blossoming of the cult of the saints, and its own canons deemed both the excommunications and canons of prior ecumenical councils as “divine” and “unshakable.”

• The Western 8th Ecumenical Council •

• The Ignatian Council of 869 or Constantinople IV •

The synod was poorly attended with only 12 bishops at the first session and it barely ever surpassed 100 bishops throughout its entire proceedings. The council made brief comments on the validity of iconography in an attempt to define a doctrinal matter so as to qualify for the status of an ecumenical council. However, its ecumenicity remains in dispute as the supposed legates of the Oriental Sees were dubious and thus the ecumenical reception remains suspect. Fr. Richard Price indicates that the papacy itself may have not regarded the synod as ecumenical, despite the council’s own claims to ecumenicity, until 200 years later when Rome needed to buttress its papal claims. The council was called primarily because Emperor Michael III had deposed Patriarch Ignatius of Constantinople and replaced him with the layman Photios. The Pope at the time of this deposition, Nicholas I, refused to recognize this action by the Emperor. A flurry of disputes occurred between Photios and Pope Nicholas I, and to sort out the issue (as well as gain back their territories in the Bulgars), the council was convoked under Pope Hadrian II in 869. Ultimately, the synod anathematized Photios, not only for his arguably illegitimate appointment to the Patriarchate, but for his own anathematization of Pope Nicholas I at a local council in Constantinople a few years prior. The Ignatian Council of 869, overall, was bipolar in its assessment of authority, as it continually wavered between justifying its decisions based on Patriarchal acceptance and simultaneously emphasizing that the Pope’s decisions can be judged by no one since he is above a council. Interestingly, its 21st canon stipulates that an ecumenical council maintains the prerogative to review disputes regarding the Papacy, enshrined the Pentarchy, and confirmed Constantinople’s second rank. This synod marked a watershed moment in the division between East and West, as the Franks now controlled the Western kingdom while the Greeks still remained in control of the East; concurrently, Western papal claims began to increase as the Western Franks’ desire to remain conciliar with the Eastern Greeks continued to wane. Ultimately, Fr. Richard Price denotes that the Church as a whole considered the Ignatian Council and its canons annulled by the subsequent Photian Council of 879 which reinstated Photios and was likely even accepted by Pope John VIII. Nevertheless, the Gregorian reforms of the 11th century inspired Western canonists to characterize this council as ecumenical so as to bolster papal prerogatives, and it is consequently considered the eighth ecumenical council in the West today.

• The Photian Schism •

• Precursor to the Great Schism •

Often viewed as the principal controversy that precipitated the Great Schism, Photios’ appointment to the Patriarchate of Constantinople in the mid-9th century ignited the East-West turmoil that would unfortunately never be resolved. In 858, Byzantine Emperor Michael III pressured Ignatius to resign from his position as Patriarch of Constantinople due to political tensions plaguing the empire. In his place, Emperor Michael appointed a politically neutral and adept laymen named Photios. To his own supporters’ consternation, Ignatius officially and willingly abdicated his office in 861, allowing Photios to singularly reign as Patriarch of Constantinople. Ironically, the local synod of 861 that validated Photios’ appointment was attended and approved by Roman legates which in reality proved a double-edged sword for the Greeks, since it validated Photios’ reign in direct contradiction to the wishes of the current Roman Pontiff (Nicholas I) while at the same time established the precedent that Roman approval was necessary for Greek Patriarchal appointments. Ultimately, Nicholas I claimed the Roman legates at the synod of 861 had gone beyond their delegated authority when they validated Photios’ appointment, and as a result Nicholas and Photios continued to spar with each other going forward.

In 863, Pope Nicholas condemned Photios primarily over jurisdictional disputes in Bulgaria, and by 867, the imperial winds had changed causing the new Byzantine Emperor Basil I to seek unity with Pope Nicholas I. Consequently, the Emperor deposed Photios and reinstated Ignatius to the patriarchal throne. In retort, citing the Filioque as one of his alleged offenses, Photios anathematized Pope Nicholas I in 867 – a manifest act of overreach by a bishop against the Roman Pontiff outside of an ecumenical council. This egregious overstep left a bad taste in the West’s mouth regarding Photios and the East for centuries, unfortunately serving as the catalyst for the Great Schism that occurred merely a century and a half later. In 869, the Ignatian Council (summarized above) was held in Constantinople and attended by Roman legates who affirmed the appointment of Ignatius, anathematized Photios, and canonized a certain degree of separation between Church and State. Pope Nicholas I’s successors, Pope Hadrian II and Pope John VIII, continued to support Patriarch Ignatius’ reign in Constantinople, principally due to the stipulation that he respect the Roman claim to jurisdiction in Bulgaria. Nevertheless, in 877, Patriarch Ignatius passed away and Byzantine Emperor Basil I promptly appointed Photios to the patriarchal position once again. The subsequent Photian Council of 879 held in Constantinople, and again approved by Roman legates, confirmed Photios’ appointment, annulled the previous Ignatian Council of 869 that had officially anathematized Photios, and forbid additions to the Creed (although it did not discuss the specific theology of the Filioque).

Pope John VIII initially was frustrated that the Emperor had not sought his approval before appointing a new Patriarch, however, he ultimately accepted the decisions of the Photian Council of 879 and rejoiced that there seemed to finally be peace in Constantinople with Photios as the new Patriarch once again. The Roman legates also secured grand statements concerning Roman primacy at the council, undoubtedly assuaging any apprehensions Pope John maintained concerning the Photian Council of 879. However, in my opinion, it remains unclear to what extent Pope John fully accepted the annulment of the Ignatian Council of 869: while it is evident that he abrogated the council’s condemnation of Photios due to the new circumstances surrounding the Patriarch that had developed within his own time, he continued to appeal to the canons of this council as basis for Church law. Regardless, neither the West nor the East viewed either the Ignatian Council of 869 or the Photian Council of 879 as the eighth ecumenical council – until it became politically expedient to do so centuries later.

During the Gregorian reforms of the late 11th century, Western theologians found the canons of the Ignatian Council of 869 helpful in substantiating the Church’s growing papal claims and bolstering its position in the lay investiture contest. Likewise, the Western canonists simply grew totally amnesiac regarding the mere existence of the Photian Council of 879 which had annulled the prior Ignatian Council of 869, and as the centuries rolled on the Ignatian Council consequently became enshrined as the eighth ecumenical council in the West. Conversely, the reality of the Photian Council’s annulment of the Ignatian Council always remained at the forefront of the East’s consciousness. Thus, for an extensive period, neither council achieved ecumenical status in the East, as not even the Photian Council qualified as ecumenical since it did not define doctrinal content. Rather, the acts of the Photian Council were merely held in high esteem in the East. It was not until the Uniate controversy of the 13th and 14th centuries that the Orthodox began to consider the Photian Council of 879 as the eighth ecumenical council, with the chasm between East and West widening and the Orthodox striving to distinguish themselves from the Uniates (who themselves actually tended to regard only the attempted reunion Council of Florence as the eighth council but nevertheless still sought union with Rome). In the end, unbeknownst to anyone at the time, the Photian Schism served as a precursor to the Great Schism which has unfortunately persisted to the present day; ironically, while Photios died in communion with Rome, the controversy he unwittingly found himself centered in would be leveraged by both the East and West to exacerbate the divorce of the two great Churches of Christendom for nearly 1,000 years.

• Timeline •

| Date | Event Summary |

| 325 | First Ecumenical Council (Nicaea I) Defined the consubstantiality of the Father and the Son and created the Nicene Creed. |

| 381 | Second Ecumenical Council (Constantinople I) Defended the consubstantiality of the Spirit with the Father and Son, relying primarily on the Triadology of the Cappadocians. The council expounded upon the Nicene Creed to form the Nicene-Constantipolitan Creed. |

| 431 | Third Ecumenical Council (Ephesus) Rome dispatched Patriarch Cyril of Alexandria to implement their Christology against the Nestorian parties. Their Christology of the Second Person of the Trinity being the one subject in Christ, in contrast to Nestorius’ two-subject Christology, ultimately won over the Emperor in the propaganda war. |

| 449 | The False Council of Ephesus II A robber council that taught Christ possessed one, singular nature after the incarnation. Ultimately, it was rejected as heretical and canonically irregular by Christendom at large. |

| 451 | Fourth Ecumenical Council (Chalcedon) Defined that Christ maintained two distinct yet united natures, human and divine, after the incarnation. It principally adopted the theology of Pope Leo’s Tome. |

| 553 | Fifth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople II) Emperor Justinian doubled-down on the condemnation of Nestorianism by posthumously anathematizing Nestorian authors of the Three Chapters. The council likewise deposed Pope Vigilius, struck him from the diptychs, and completed the council in his absence. |

| 649 | The Lateran Synod Convoked by St. Maximus and Pope Martin in order to condemn the notion that Christ maintained only one will and one energy after the incarnation. It purported to be ecumenically binding due to Papal ratification, but was not subsequently considered ecumenical by East or West to this day. |

| 681 | Sixth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople III) Ratified the Christology of St. Maximus as articulated at the Lateran Synod, which defined that Christ maintained two distinct wills and two distinct energies based in their respective natures after the incarnation. Pope Agatho made strong papal claims, yet the council ironically posthumously anathematized Pope Honorius for his Monothelitism. |

| 692 | Quinisext Council of Trullo Adopted in the East as an extension of the Fifth and Sixth Ecumenical Councils, as it supplemented those councils with disciplinary canons. The West never adopted the council but viewed it primarily as an Eastern disciplinary synod. The consciousness of Emperors as the fulfillment of the Kings of Judah was demonstrably full-blown. |

| 754 | False Council of Hieria In the midst of an iconoclastic imperial regime, the council condemned the veneration of iconography. |

| 787 | Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicaea II) The imperial winds changed, prompting a new council to be convened in order to defend iconographic veneration. The council invalidated the Council of Hieria based on the fact that it did not obtain the assent of all the Patriarchates. It defended iconographic veneration based on the purported apostolic origins of the practice and on the rationale that the veneration passed beyond the image to the prototype. |

| 861 | Amid political pressure, Patriarch Ignatius of Constantinople resigned and Photios then singularly reigned as Patriarch. |

| 867 | The Emperor changed his mind and sought closer union with Pope Nicholas I who had supported Ignatius. Consequently, the Emperor deposed Photios and reinstated Ignatius to the Patriarchate. |

| 869 | The Ignatian Council of 869 Photios was anathematized, Ignatius’ reappointment was confirmed, and the papacy claimed to be above the judgment of an ecumenical council. The council itself claimed ecumenicity and maintained dubious Patriarchal ratification. |

| 877 | Patriarch Ignatius died and Photios was subsequently reappointed to the Patriarchate by the Emperor without the Pope’s consultation. |

| 879 | The Photian Council of 879 The council confirmed Photios’ reappointment, anathematized those who held to the decisions of the Ignatian Council of 869, forbid additions to the Nicene-Constantipolitan Creed, the Roman legates accepted the anathematization, and Pope John VIII ultimately accepted, at a minimum, the council’s abrogation of the Ignatian Council and reappointment of Photios. |

| 1054 | Primarily facilitated by jurisdictional disputes in Bulgaria, legates of Rome and Constantinople excommunicated each other citing diverging liturgical practices, as well as disagreements concerning papal primacy and the procession of the Holy Spirit. This is often marked as the date of the Great Schism. |

| 1073 | Pope Gregory VII assumed the Roman episcopate and implemented substantial Western reforms to bolster papal authority in the midst of the investiture contest. During this time period, Western Canonists lost memory of the Photian Council and instead considered the Ignatian Council as ecumenically binding, allowing them to bolster their papal claims through the council’s robust papal views. |

| 1274 | Second Council of Lyons The first failed attempted reunion council between East and West. Some Eastern bishops, known as the Uniates, crossed over into communion with Rome; however, the majority remained out of union. |

| 1449 | Council of Florence The second failed attempted reunion council between East and West. Again, some more Eastern bishops crossed over into communion with Rome, however, the majority remained out of union. |

| 1517 | Martin Luther catalyzed the Western Reformation. |

| 1965 | The Patriarch of Rome and the Patriarch of Constantinople lifted the excommunications of 1054 but have not yet reunited. |

†

Leave a comment