• Table of Contents •

- Table of Contents

- Preface | Explanation of Concepts

- APOSTOLIC PERIOD:

- ANTE-NICENE PERIOD:

- ECUMENICAL PERIOD:

- 325 AD | Ecumenical Council of Nicaea I

- 325 – 373 AD | Persecution of St. Athanasius

- 340 AD | Apostolic Canons

- 343 AD | Council of Sardica

- 350 – 389 AD | Cappadocian Fathers

- 362 AD | Didymus the Blind

- 375 AD | St. Jerome’s Papalism

- 380 AD | Empire’s Adoption of Christianity

- 381 AD | Ecumenical Council of Constantinople I

- 382 AD | Pope Damasus’ Synod

- 415 AD | St. Augustine’s Triadology

- 417 AD | Pope Zosimus’ Papalism

- 431 AD | Ecumenical Council of Ephesus

- 449 AD | Robber Synod of Ephesus II

- 451 AD | Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon

- 476 AD | Fall of Rome

- 484 AD | Acacian Schism

- 495 AD | Decretal of Pope Gelasius I

- 519 AD | Formula of Hormisdas

- 553 AD | Ecumenical Council of Constantinople II

- 589 AD | Third Council of Toledo

- 590 AD | “Ecumenical Bishop” Dispute

- 640 AD | St. Maximus’ Letter to Marinus

- 649 AD | Lateran Synod

- 681 AD | Ecumenical Council of Constantinople III

- 692 AD | Quinisext Council (Trullo)

- 749 AD | St. John of Damascus’ Theology

- 754 AD | False Council of Hieria

- 787 AD | Ecumenical Council of Nicaea II

- 800 AD | Coronation of Charlemagne

- 863 AD | Photian Schism

- 869 AD | Ignatian Council

- 879 AD | Photian Council

- GREAT SCHISM PERIOD:

- 1019 AD | Pope Struck from Diptychs

- 1054 AD | Rome & Constantinople Excommunicate

- 1076 – 1124 AD | Investiture Controversy

- 1095 AD | First Crusade

- 1204 AD | Sack of Constantinople

- 1215 AD | Western Ecumenical Council of the Lateran IV

- 1270 AD | St. Thomas Aquinas’ Triadology

- 1274 AD | Western Ecumenical Council of Lyons II

- 1285 AD | Eastern Council of Blachernae

- 1330 AD | Gregory Palamas’ Triadology

- 1351 AD | Eastern Palamite Synods

- 1431 AD | Western Ecumenical Council of Florence

- 1453 AD | Fall of Constantinople

- 1517 AD | Protestant Reformation

- 1534 AD | The Anglican Church

- 1545 AD | Western Ecumenical Council of Trent

- 1569 AD | Union of Brest

- 1643 – 1672 AD | Confession of Jassy & Synod of Jerusalem

- 1724 AD | Melkite Catholics

- 1848 AD | Pope Pius IX & the East

- 1854 AD | Immaculate Conception

- 1870 AD | Western Ecumenical Council of Vatican I

- 1875 AD | The Bonn Conference

- 1895 AD | The Patriarchal Encyclical

- 1950 AD | Assumption of Mary

- RAPPROCHEMENT PERIOD:

- 1962 AD | Western Ecumenical Council of Vatican II

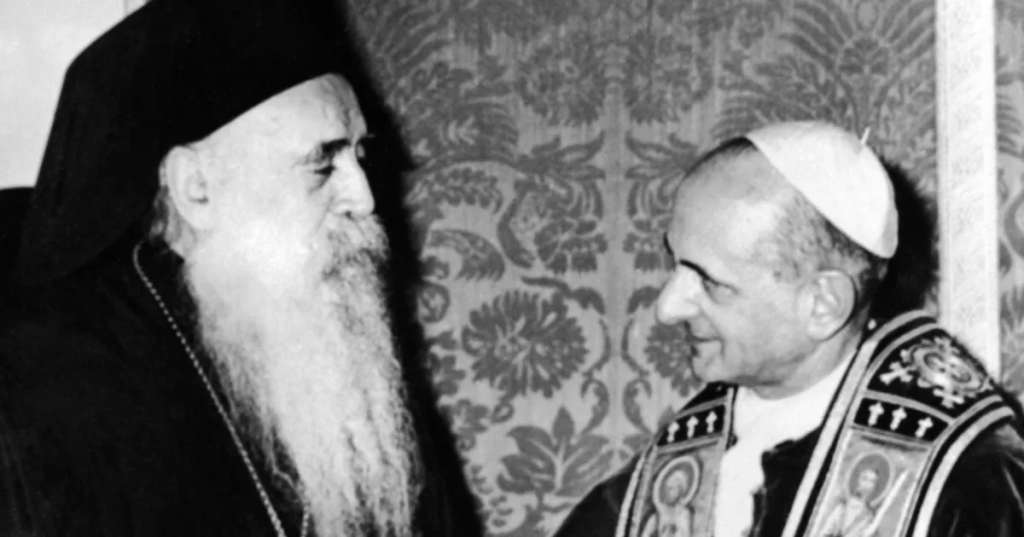

- 1965 AD | Excommunications Lifted

- 1993 AD | Balamand Declaration

- 1995 AD | JPII’s Filioque Clarification

- 2016 AD | Eastern Council of Crete

- 2007 – 2023 AD | Dicastery Documents

- 2024 AD | Treatise on The Bishop of Rome

- 2025 AD | Anniversary of Nicaea

- X | Prayer for Reunion

• Preface •

Overview: The following is an outline of the most significant monuments of ecclesiastical history pertinent to the relationship between the East and West, with each date entry containing primarily a summary of the events’ relevance to the Churches’ respective positions. It will certainly be observed that my analysis focuses heavily on the various Ecumenical Councils and attempted reunion synods, as they exhibit head-to-head clashes of Eastern and Western theology. There, undoubtedly, remains nearly infinite content on this subject, but I have ventured to compile that which I have found to be the most pivotal information in examining the Schism. Hopefully, this will serve as both a practical and extensive resource for the inquirer.

Concepts: Of particular note through the entire enterprise are the two principle theological issues undergirding the Great Schism, namely the Filioque and the prerogatives of the Papacy. Latin for “and the Son,” the Filioque is a Western addition to the Nicene Creed which highlights the Son’s unity with the Father through their subsistence as a single “cause” of the Spirit’s Person from all eternity. To clarify, theologians speak of the eternal relations of the Divine Persons, not to characterize them as “coming into existence,” but to distinguish the Persons based on their respective relations of dependence while eternally existing. Both East and West affirm that the Father is eternally “caused” by (or is dependent on) neither the Son nor the Spirit but simply retains the divine essence by virtue of himself; however, the Son and Spirit source their divine essence in the Father and in this sense the Father is often described as “cause” or “principle.” The West views the Son as subsisting notionally prior to the Spirit, and as a consequence of the divine unity, also as being with the Father the one “cause” of the Spirit. The East balks at this theology and its corresponding Filioque insertion, as they remain uncertain how exactly the West is utilizing the term “cause,” since the Eastern Fathers normatively apply it strictly to the Father in order to denote him as the ultimate source of the divine essence.

Although the Filioque will be the central theological issue cited by the East for the Schism, perhaps at the root of the whole dispute is in reality the nature of the Papacy. Western Christianity (Catholicism) asserts that the bishop of Rome uniquely inherits divinely appointed Petrine authority through its lineage from the Apostle himself, while Eastern Christianity (Orthodoxy) ultimately posits that the Roman bishop’s prerogatives are largely pragmatic delegations by the universal Church. The former view entails papal infallibility as a consequence of the Pope remaining the final decision maker for an indefectible Church through Christ’s bestowing of the keys on Peter, while the latter paradigm understands the Church to simply have codified an administrative priority to the bishop of Rome with only the Church expressed through conciliarity subsisting infallibly. As a result, the West will repeatedly emphasize the theological necessity of the Pope’s Petrine primacy, while the East will seek to embody the synodal authority entrusted to the college of Apostles as a whole.

Personal Analysis: In short, my own conclusion has been that the Filioque and Papacy remain logical necessities which the Orthodox have been unable to persuasively and coherently overcome. Although patristic evidence in the Ante-Nicene period for the papalism of Vatican I seems often exaggerated and decontextualized, throughout all ages the bishop of Rome has been regarded as a Petrine figure with unique prerogatives, the fullness thereof explicated as early as the 5th century. Despite the seemingly sophomoric tone of the position, after years of in-depth study, it has only grown more apparent to me that the See of Constantinople subsisted frequently as a puppet to the Eastern Emperor’s agenda which the head of the Church, the Pope, routinely had to constrain. This reality is readily observed in the case of Photios who initiated the East’s campaign against the Filioque in order to justify his imperial appointment to the Patriarchate against both canonical and papal guidance. The whole debacle arguably foreshadows the Reformation’s own game-plan of incoherently repudiating Rome’s doctrine of justification so as to rationalize perpetual schism. Ultimately, however, the East has indeed preserved a legitimate conciliar emphasis consonant – perhaps, in spite of appearances – with the Western primatial underpinnings, as they both respectively instantiate the Trinitarian One and the Many. More can be read on my position in “The Fiat of Conversion.”

With each Church embodying the glories of the Divine in unique and complementary modes, the Great Schism between East and West is perhaps the most tragic development in the past 2,000 years. This scandalous divorce has exerted egregious damage, not only on the Church, but on the entire world itself. God’s people will never be whole until we can once again “breathe with both lungs.”

• Apostolic Period •

NOTE: Not all events outlined in this section technically involve the Apostles, but the designation is used out of convenience, with the period ending once John dies on Patmos.

• 0 AD | Christ is Born •

Christ is born to the Virgin Mary, ushering in the New Creation and eventually the founding of his Kingdom (the Church).

• 33 AD | Christ’s Ministry & the Keys •

The Crucifixion, Resurrection, Ascension, and Pentecost take place as documented in the Gospels.

Before his crucifixion, knowing that he will subsequently ascend to heaven, Christ delegates to Peter the keys to his kingdom (the Church) as recorded in Matthew 16:18-19:

“And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

Christ, likewise, relegates similar authority to the entirety of the Apostles in Matthew 18:18-19:

“Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven. Again, truly I tell you that if two of you on earth agree about anything they ask for, it will be done for them by my Father in heaven.”

The former passage will serve as the basis for Western Papal authority, while the latter will be employed to promote synodality in the East.

• 42 AD | Church of Rome Founded •

Through their missionary efforts, Peter and Paul found numerous churches throughout the Roman Empire, and most notably the Church in Rome.

• 50 AD | Council of Jerusalem •

As detailed in the Book of Acts, the Apostles convene the Council of Jerusalem in order to determine that circumcision is not required for initiation into the New Covenant.

Peter’s decisive declaration at the Council will be appealed to by Rome as evidence for papal supremacy, while the Apostolic assembling of a council will be cited by the East as endorsing synodal ecclesiology.

• 64 AD | Peter’s Martyrdom in Rome •

Peter is crucified by the Roman Emperor Nero in the city of Rome. Tradition maintains that he requests to be crucified upside down, as he feels unworthy to die exactly as Christ.

Subsequent bishops of Rome ultimately claim to succeed in Peter’s bishopric and corresponding Petrine primacy due to reigning in the final location that he exercised his episcopal ministry.

Relatedly, the Vatican to this day purports to be built directly above Peter’s bones.

• 70 – 96 AD | Siege of Jerusalem •

The temple of Jerusalem is destroyed by the Romans, with subsequent Church Fathers interpreting this event as God’s judgment on the Jews for their rejection of the Messiah. The Catholic Church now stands as the Third and Final Temple.

Of further note around this time period (without exacting dating):

• Clement I, bishop of Rome, writes to the Church of Corinth outside of his immediate province to settle doctrinal unrest. The West appeals to this incident as evidence for papal universal jurisdiction, while the East interprets this merely as an example of pragmatic developments in authority for prominent bishoprics across the Church as a whole.

• The Didache is composed, which purports to be a catechism of the Apostles. Noteworthy aspects include a description of the liturgy of the mass, instructions on partaking in the Eucharist, and prohibitions against abortion.

• 99 AD | Death of the Apostle John •

The Apostle John, the last living apostle, dies on the Island of Patmos where he also had written the Book of Revelation.

• Ante-Nicene Period •

NOTE : In the centuries prior to the convocation of the first Ecumenical Council of Nicaea, the Church functions principally in localities, with disciplinary and doctrinal regulations being established by regional synods of bishops. Yet, disputes are not exclusively provincial, as individuals occasionally appeal to more prominent bishops outside their own localities when in conflict with the resident clergy. Episcopates with apostolic origins maintain a greater degree of respect due to the likelihood they have retained the teachings of their founders, garnering the appeals of Christians amidst ecclesiastical disputes. The city of Rome embodies the pinnacle of these privileges as its church has been founded by the apostles Peter and Paul while also remaining the most renowned metropolis in the Empire.

• 120 AD | First Easter Conflict •

St. Polycarp, the bishop of Smyrna and in fact disciple of the Apostle John himself, informs Pope Anicet that the Apostle had instructed him to celebrate Easter according to the Jewish date, with Pope Anicet retorting that Sunday observance has been the ancient tradition of the Roman Church since its founding. The two prominent figures agree to let each custom provincially persist.

• 140 AD | St. Ignatius of Antioch •

St. Ignatius of Antioch, as a notable bishop and alleged disciple of the Apostle John, writes final instructions to various churches outside his immediate jurisdiction on his way to his martyrdom, while famously describing Rome as the ultimate church presiding in love and possibly even implying her precedence over the universal Church:

“Ignatius . . . to the Church also which holds the presidency, in the location of the country of the Romans, worthy of God, worthy of honor, worthy of blessing, worthy of praise, worthy of success, worthy of sanctification, and, because you preside in charity, named after Christ and named after the Father. . . You [the Church in Rome] have envied no one, but others you have taught. I desire only that what you have enjoined in your instructions may remain in force.”

Letter to the Romans, 1:1 [A.D. 110]

• 180 AD | St. Irenaeus of Lyon •

St. Irenaeus, bishop of Lyon, produces Against Heresies, combatting various gnostic sectarians. Throughout his treatise, he defends orthodoxy primarily on the basis of its teachings emanating from churches that can trace their episcopates to apostolic founders in contrast to the novelty of the gnostic doctrines and leaders. He appeals utmost to the church in Rome as witness for his doctrines due to her dual apostolicity, as well as her imperial prominence with unrivaled connection to Christians across the world:

“But since it would be too long to enumerate in such a volume as this the succession of all the churches, we shall confound all those who, in whatever manner, whether through self-satisfaction or vainglory, or through blindness and wicked opinion, assemble other than where it is proper, by pointing out here the successions of the bishops of the greatest and most ancient church known to all, founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul, that church which has the tradition and the faith which comes down to us after having been announced to men by the apostles. With that church, because of its superior origin, all the churches must agree, that is, all the faithful in the whole world, and it is in her that the faithful everywhere have maintained the apostolic tradition.”

Against Heresies, 3:3:2 [A.D. 189]

Western apologists often cite St. Irenaeus’ description of the “superior origin” of the Roman church as evidence for early papalism. However, in context it seems clear that he is simply referring to her uniquely dual apostolic foundation, as opposed to a divinely mandated founding.

Of note, tradition holds St. Irenaeus to have heard the teaching of St. Polycarp, the disciple of the Apostle John.

• 190 AD | Second Easter Conflict •

Polycrates of Ephesus assembles his own synod to enshrine the Jewish date of Pascha as the official practice of his church, claiming, like St. Polycarp before him, that the custom had been received from the Apostle John. Pope Victor promptly excommunicates him and his followers in the Asian Churches under the charge of heterodoxy. Yet, Polycrates remains headstrong in his opposition:

“I am not afraid of your terrifying words, Victor, for I have lived sixty-five years in the Lord, and have met with the brethren throughout the world, and have gone through every Holy Scripture, and those greater than I have said, ‘We ought to obey God rather than men.’”

Laurent Cleenewerck. His Broken Body : Understanding and Healing the Schism between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. p. 154

For the sake of unity, a number of bishops urge Pope Victor to reconsider his excommunications and instead tolerate a diversity of customs as had his predecessors, with historian Eusebius indicating that St. Irenaeus, among others, “sternly rebuked” him for his intensity. Ultimately, the Asian Churches will retain their practice until the later Council of Nicaea universally implements the Roman observance.

Both East and West see in this dispute evidence for their respective ecclesiologies, as the East appeals to Polycrates’ refusal to submit to the Papacy while the West underscores Pope Victor’s authority to excommunicate churches in Asia outside his immediate province.

• 250 AD | Baptism Controversy •

St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, and Firmilian, bishop of Caesarea Mazaca, describe Pope Stephen’s condemnations of rebaptism for certain schismatics as heretical, with Firmilian even positing that the Pope has cut himself off from the Church as a result.

St. Cyprian understands the See of Peter – as in, those episcopates with legitimate apostolic lineages – to be the source of union in the Church, in contrast to the novel episcopate established by the heretical Novations plaguing the Church. Indeed, he explicitly views all bishops as equal and normatively restricted jurisdictionally to their dioceses, the bishop of Rome being included:

“He arranged by His authority the origin of that unity, as beginning from one. Assuredly the rest of the apostles were also the same as was Peter, endowed with a like partnership both of honor and power; but the beginning proceeds from unity… In the administration of the Church each bishop has the free discretion of his own will, having to account only to the Lord for his actions. None of us may set himself up as bishop of bishops, nor compel his brothers to obey him; every bishop of the Church has full liberty and complete power; as he cannot be judged by another, neither can he judge another.”

Treatise 1, On the Unity of the Church.

The East, at various points throughout history, will leverage the Cyprian understanding of the episcopacy in their battles with the West. Conversely, many Western apologists will cite St. Cyprian’s following emphasis on unity with “the See of Peter” as evidence for their papalism:

“After such things as these, moreover, they still dare — a false bishop having been appointed for them by, heretics— to set sail and to bear letters from schismatic and profane persons to the throne of Peter, and to the chief church whence priestly unity takes its source; and not to consider that these were the Romans whose faith was praised in the preaching of the apostle, to whom faithlessness could have no access. But what was the reason of their coming and announcing the making of the pseudo-bishop in opposition to the bishops?”

Epistle 54.

Despite the strength of this quote, in light of his other writings and explicit theological tension with Pope Stephen, I personally hold the Western apologetics to implicitly project an unrealistic amount of cognitive dissonance onto St. Cyprian. For, it is simpler to understand the Saint as merely defending the vitality of legitimate apostolic lineage rooted in the Petrine episcopate, similar to the perspective of St. Irenaeus before him. Otherwise, one would need to propose that St. Cyprian views Pope Stephen as a unique source of unity while yet, according to the Saint himself, preaching heresy and meriting active opposition.

• 312 AD | Constantine’s Conversion •

Emperor Constantine converts from paganism to Christianity, the first Roman Emperor to enter into the Church.

• 313 AD | Edict of Milan •

The Edict of Milan is issued by Constantine, legalizing Christianity, effectively ending the period of persecution in the early Church.

• 324 AD | Eusebius’ History •

Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea Maritima and in many respects Constantine’s propagandist, writes his Ecclesiastical History, tracing the events of the Church primarily through the pontificates of each Roman bishop.

• Ecumenical Period •

NOTE: The Church moves from a period of persecution and mere local councils into imperial synergism and worldwide disputes being ecumenically addressed.

• 325 AD | First Ecumenical Council •

The Council of Nicaea I is convened at the behest of Emperor Constantine in order to settle the empire-wide unrest regarding the nature of Christ. Ultimately, the world’s bishops assemble, with Pope Sylvester sending legates on his behalf, to define that Christ is consubstantial with the Father based on his eternal generation (or begetting) from the Father. The Nicene Creed is accordingly formulated to encapsulate the Church’s dogmas, including that the Son is “begotten of the Father.” This council sets the precedent for resolving worldwide theological disputes through ecumenical gatherings of bishops (imitating the apostolic Council of Jerusalem), summoned in synergism with the Empire.

Notably, Nicaea codifies in its sixth canon both the primacy of the Roman bishop, as well as the administrative office of Metropolitans with limited jurisdiction – an office which would gradually blossom into the concept of Patriarchs.

“Let the ancient customs in Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis prevail, that the Bishop of Alexandria have jurisdiction in all these, since the like is customary for the Bishop of Rome also. Likewise in Antioch and the other provinces, let the Churches retain their privileges. And this is to be universally understood, that if any one be made bishop without the consent of the Metropolitan, the great Synod has declared that such a man ought not to be a bishop. If, however, two or three bishops shall from natural love of contradiction, oppose the common suffrage of the rest, it being reasonable and in accordance with the ecclesiastical law, then let the choice of the majority prevail.”

Council of Nicaea I, Canon 6.

Less controversially by this period, Nicaea officially mandates the Roman Easter date as the universal practice of the Church – vindicating Popes Anicet and Victor.

• 325 – 373 AD | St. Athanasius •

St. Athanasius, Patriarch of Alexandria, relentlessly defends Nicene Christology against nonconforming Arians who deny the consubstantiality of Christ’s nature with the Father. He faces imperial persecution for his orthodox views and is exiled four times by Arian emperors, while in contrast being unwaveringly supported by the bishop of Rome.

His writings emphasize unity among the Divine Persons and arguably set the stage for the Triadology of the Filioque. The spurious Athanasian Creed, promulgated in later centuries, seeks to embody his Triadology and potentially teaches the Filioque.

• 340 AD | Apostolic Canons •

The Apostolic Canons are composed, which purport to be ecclesiastical protocols enshrined by the Apostles themselves. In the Middle Ages, the West will ultimately accept 50 of the canons as binding, while the East will receive 85 of the canons at the Quinisext Council (Trullo) of 692.

The most significant canon will be Canon 34, accepted by both East and West, which dictates that the primate should not legislate anything without the synergism of the synod (and vice versa). In context, the canon implicitly bases this synergism of the primate and the synod on the One and the Many intrinsic to the Trinitarian relations. While technically only describing protocols on a local level, it will come to frame the context of the universal Papal and Patriarchal debates between East and West.

• 343 AD | Council of Sardica •

An attempt is made to convene a second ecumenical council, as St. Athanasius continues to wage a Christological battle in the Eastern half of the Church. Ultimately, he is deposed by those whom he claims are either Arian or Sabellian heretics in the East. The Council of Sardica attempts to reconcile the Western and Eastern Churches, as well as round out Trinitarian terminology even further as a result. Sardica vindicates St. Athanasius while also being a catalyst for the first schism between East and West. While the synod is never received as a second ecumenical council, it evolves to be universally considered an addendum to the Council of Nicaea (mostly due to historical error by Western canonists).

Most importantly, based explicitly in honor of Peter himself, the synod establishes the “Sardican privilege” of the bishop of Rome, through which bishops across the world may appeal to him for a retrial of a local dispute and, if approved by the Pope, the local bishops would need to re-examine the disputed case. Notably, the Pope himself would not be the final judicator – simply an assessor of whether a local retrial should commence in the original province of the dispute.

• 350 – 389 AD | Cappadocian Fathers •

The Cappadocian Fathers (St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory of Nyssa, and St. Gregory of Nazianus) compose several writings on the Persons of the Trinity, emphasizing the Father as “cause” of the Son and Spirit. The East will heavily adopt this paradigm and cite these Fathers in later Filioque debates, especially St. Gregory of Nazianus’ proposition that the difference between procession and begottenness cannot be known.

• 362 AD | Didymus the Blind •

Didymus the Blind, a pupil of Origen and potentially head of the Catechetical School of Alexandria, seems to have articulated a Filioque position:

“…For neither has the Son anything else except those things given him by the Father, nor has the Holy Spirit any other substance than that given him by the Son.”

The Holy Spirit, 37 [A.D. 362]

The Church never comes to recognize Didymus as a Saint due to his Origenism, but in his time he appears to have been an influential theologian.

• 375 AD | St. Jerome’s Papalism •

Amidst mounting theological tension between the East and West regarding the application of the terms “hypostasis” and “ousia,” the great Western Saint Jerome writes to the Bishop of Rome:

“…My words are spoken to the successor of the fisherman, to the disciple of the cross. As I follow no leader save Christ, so I communicate with none but your blessedness, that is with the chair of Peter. For this, I know, is the rock on which the church is built! This is the house where alone the paschal lamb can be rightly eaten. This is the Ark of Noah, and he who is not found in it shall perish when the flood prevails.”

Letter 15.

At this juncture, the West understands the term “hypostasis” to be indicative of nature instead of person, and thus the Eastern/Cappadocian usage of “three hypostases” in the Trinity denotes Arianism to the Western mind.

• 380 AD | Adoption of Christianity •

Emperor Theodosius officially enshrines Christianity as the imperial religion. He is the last emperor to rule the entirety of the Roman Empire before its permanent split between Western and Eastern halves.

• 381 AD | Second Ecumenical Council •

A local synod is convened in Constantinople, without any papal representation, which purports to be the second ecumenical council of the universal Church. It will in fact ultimately be received as such readily in the East but begrudgingly in the West.

The impetus for the council is twofold: the ongoing dispute regarding the term “hypostasis” (as opposed to “ousia”) being applied to Trinitarian Persons and the nature of the Holy Spirit. The Ecumenical Council of Constantinople I, as it comes to be termed, adopts the Cappadocian “hypostasis” paradigm in order to defend the consubstantiality of the Holy Spirit with the Father, and by implication the Son, through inserting into the Nicene Creed the phrase that the “Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father.” Thus, as the Son’s divinity is preserved through his eternal begetting from the Person (hypostasis) of the Father, so is the Spirit considered divine in nature (ousia) due to his eternal procession from the Person (hypostasis) of the Father.

Controversially, the Council’s third canon novelly establishes Constantinople as a Patriarchate, and indeed one in rank above all other Patriarchs besides Rome based solely on its status as the imperial Capitol. The second canon also, interestingly, dictates that all bishops should not adjudicate or legislate outside their dioceses, nor Patriarchs outside their regions, without explicitly delineating any exceptions for the Roman bishop.

• 382 AD | Pope Damasus’ Synod •

In response to Constantinople I, Pope Damasus convokes a local synod and defines that the Pope indeed inherits his authority, not from any conciliar decree or political accommodation, but rather from the voice of the Lord himself in Matthew 16:18.

Furthermore, he outlines the ranking of the Patriarchs based on their respective Petrine and apostolic lineages, entirely excluding Constantinople from the list. Over time, however, Rome comes to accept Constantinople as second in rank among the Patriarchs, as well as the theological definitions outlined at the Council of Constantinople I as being ecumenical. Yet the West never retracts the understanding that the Pope uniquely receives the charism of universal primate from God alone.

The East will subsequently start to claim that St. Andrew founded the episcopate in Constantinople in order to garner an apostolic pedigree and legitimize their ascension to the second ranking Patriarchate ahead of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.

• 415 AD | St. Augustine’s Triadology •

St. Augustine produces his treatise “On the Trinity” in which he expounds on the divine unity and simplicity arguably seeded in St. Athanasius’ Triadology. He posits that the names of the Persons, their temporal relations, and various earthly analogies indicate the Persons’ respective notional priorities of origins and consequently their eternal relations. It is nearly universally recognized that on the basis of this reasoning St. Augustine teaches the Filioque throughout his work:

“If, therefore, that also which is given has him for a beginning by whom it is given, since it has received from no other source that which proceeds from him; it must be admitted that the Father and the Son are a beginning of the Holy Spirit, not two Beginnings; but as the Father and Son are one God, and one Creator, and one Lord relatively to the creature, so are they one Beginning relatively to the Holy Spirit. But the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are one Beginning in respect to the creature, as also one Creator and one God.”

Hippo, A. O. (2012). On the Trinity. pp. 247

The Augustinian position will serve as the primary foundation for the Western understanding of the Trinity moving forward.

• 417 AD | Pope Zosimus’ Papalism •

Pope Zosimus writes to the African churches, commending their respect for the authority of the Roman See and underscoring his papal prerogatives:

“…for you have confirmed that reference must be made to our judgment, realizing what is due to the Apostolic See, since all of us placed in this position desire to follow the Apostle, from whom the episcopate itself and all the authority of this name have emerged. …[the Fathers] thought that nothing whatever, although it concerned separate and remote provinces, should be concluded unless it first came to the attention of this See, so that what was a just proclamation might be confirmed by the total authority of this See, and from this source (just as all waters proceed from their natal fountain and through diverse regions of the whole world remain pure liquids of an uncorrupted source), the other churches might assume what they ought to teach, whom they ought to wash, those whom the water worthy of clean bodies would shun as though defiled with filth incapable of being cleansed.”

Epistle 29, “In Requirendis,” Jan. 27, 417.

He evidently considers his See’s authority as deriving from Peter, maintaining some degree of universal jurisdiction (debatably sequestered or un-sequestered), and possessing at least a propensity – if not an intrinsic charism – for inerrant teaching. The parallels to later Vatican I ecclesiology are marked.

• 431 AD | Third Ecumenical Council •

The third universal assembly of the Church is convened, the Ecumenical Council of Ephesus, as a debate grips the Empire concerning the number of hypostases (persons) that the incarnated Son subsists as. The arch-heretic Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, proposes that both a human person and a divine person simultaneously exist in Christ, in contrast to orthodox Christology which affirms that the singular divine hypostasis of the eternal Word simply assumed a human nature. St. Cyril’s use of the title “God-bearer,” or “Mother of God,” for Mary ignites this Church-wide dispute, as he rightly understands the divine Son to be the singular subject of all actions performed through the incarnation – including being conceived in Mary. The third Ecumenical Council of Ephesus universally ratifies the singular divine hypostasis of Christ, with Nestorian dissidents largely originating in Antioch and spreading throughout Assyria.

• In response to the Nestorian conflation of person and nature, Pope Celestine convenes his own local council in 430 AD to ratify the Cyrillian christology and depose Nestorius. The Pope, in fact, considers it within the scope of his authority to nullify Nestorius’ own excommunications of orthodox bishops and concurrently admonishes the people of Constantinople to reject the Nestorian clergy throughout the Empire. Moreover, the Council of Ephesus itself ultimately requests judgment to Celestine of its excommunications of Nestorian figures, demonstrating the Pope’s authority to review such conciliar decisions.

• Despite Pope Celestine’s own local council addressing Nestorianism, Christendom does not consider the issue entirely settled. In his letter to the Emperor, Celestine himself legitimizes the convoking of an ecumenical council in order to confront the controversy:

“But in virtue of episcopal office, each of us as far as he is able devotes his labor to the glory of this heavenly responsibility, and we are present at the council you have ordered in those whom we send, while we entreat your piety, as we appeal to the divine judgment, that your mildness should not give any scope to unruly novelty… For success in everything else will follow if priority is given to preserving the things of God, as being still more dear.”

Price, Richard, and Thomas Graumann. The Council of Ephesus of 431. p. 204

• Pope Celestine’s legates explicitly claim Petrine succession as near-assurance of their orthodoxy and underscore the council’s responsibility to remain in union with the Pope as the head of the Church:

“It is doubtful to no one, rather it has been known in all ages, that the holy and most blessed Peter, the leader and head of the apostles, the pillar of the faith, and the foundation of the catholic church, received the keys of heaven from our Lord Jesus Christ the savior and redeemer of the human race, and was given the power to bind and unloose sins, and that he lives and performs judgment, until now and always, through his successors. In accordance with this system, his successor and representative, our holy and most blessed pope Bishop Celestine, has sent us to this council as substitutes for his presence…”

Price, Richard, and Thomas Graumann. The Council of Ephesus of 431. p. 378

• St. Cyril is viewed as the main theological authority who the council appeals to – potentially by virtue of his role as effectively the Pope’s delegate. Notably, the bishops view the Nicene Creed of 325 as inerrant and continually seek to ensure St. Cyril’s theology aligns with the dogma contained therein.

• The council refers to the Emperor also as the head of the Church and yet his legates readily understand they are to refrain from interfering directly in ecclesiastical matters at the synod, highlighting the hyperbolic and honorific nature of the Byzantine language.

• Interestingly, Ephesus anathematizes the christology detailed in a proposed Nestorian creed, which remarkably appears to contain an explicit denial of the Filioque position: “…we do not consider [the Spirit] to be the Son nor to have received existence through the Son.” Yet, the council refrains from characterizing this denial of the Filioque as either heresy or orthodoxy, but instead the clause remains completely unaddressed in the council’s proceedings.

• The council’s 7th canon establishes, “that it is unlawful for any man to bring forward, or to write, or to compose a different Faith as a rival to that established by the holy Fathers assembled with the Holy Ghost in Nicaea.” The East will appeal to this canon as the basis for its rejection of the creedal insertion of the Filioque, while the West will interpret this canon as simply prohibiting alterations to the the Nicene Creed’s overall meaning, not its exact contents, as the Council of Constantinople I indeed expounds upon the original creed and is yet accepted by both East and West.

• Nestorian dissidents spread across Assyria and ultimately form the Assyrian Church of the East. This becomes the religion dominant in the Persian Empire, as well as China later on in history.

• 449 AD | Robber Synod of Ephesus II •

In the wake of the Council of Ephesus of 431, bishops in the East begin to posit that not only is Christ one Person but that after the incarnation he also consists of only one nature, as an over-extrapolation of St. Cyril’s unified christology. St. Cyril’s own successor at Alexandria, Dioscorus, becomes the main proponent of this heresy, alongside a prominent bishop in Constantinople named Eutyches. The impetus behind their theology resides in a concern that upholding two natures in Christ is simply a continuation of the dual-hypostases heresy indicative of the Nestorian position, and consequently Dioscorus and Eutyches convene the robber council of Ephesus II in 449 AD to condemn the dyophysite perspective. The synod rejects the input of the Pope’s legates who oppose these monophysite conclusions, and the heretical bishops allegedly even murder orthodox Patriarch Flavian during the proceedings, resulting in Pope Leo and the Western Emperor Valentinian III repudiating Ephesus II in total.

• Ephesus II never receives ecumenically binding status in the imperial Church due to its failure to garner papal ratification, a reality that Western apologists will continually highlight in ecclesiastical debates over the ecumenicity.

• While the Eastern Emperor Theodosius II himself ratifies the robber council, facilitating a brief schism between East and West, his successor Marcian eventually institutes a pro-Roman posture and reinstates the previously excommunicated orthodox bishops to their episcopates.

• 451 AD | Fourth Ecumenical Council •

Amidst the aftermath of the previous robber council, Pope Leo considers the East’s eventual acceptance of his Tome explicating orthodox dyophysite christology as sufficient, as he understandably maintains an aversion to additional councils after the egregious debacle of Ephesus II. Regardless, Emperor Marcian pursues the convocation of another ecumenical council to alleviate all doubts in the East concerning the christological issue. Accordingly, in 451 AD, the fourth Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon is convened by the Emperor to universally condemn the heretical monophysites both for their non-canonical conduct and their heretical theology at the robber council of Ephesus II. Chalcedon universally ratifies the dual nature of Christ, with monophysite dissidents largely in Alexandria developing into the Oriental Orthodox communion.

• Chalcedon officially rejects the robber council of Ephesus 449 on the basis that it failed to abide by canonical law and never garnered papal ratification.

• Pope Leo and his legates present markedly strong papal claims to justify their theological conclusions and compel the council’s excommunication of Dioscorus:

“Therefore the holy and most blessed pope, the head of the universal church, through us his representatives and with the assent of the holy council, endowed as he is with the dignity of Peter the Apostle, who is called the foundation of the church, the rock of faith, and the doorkeeper of the heavenly kingdom, has stripped him of episcopal dignity and excluded him from all priestly functions. What remains is for the venerable council assembled to pronounce, as justice bids, a canonical verdict against the aforesaid Dioscorus.”

Price, Richard, and Michael Gaddis. The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon. p. 70

Indeed, the strength of Leo’s own papalism is even of such a degree that Vatican II ultimately rejects some of his perspectives – specifically the notion that the episcopate’s jurisdiction originates in the papacy instead of directly in Christ.

• The council fathers exclaim that “Peter speaks through Leo,” after examining his Tome. In contrast to typical characterizations among Western apologists, the bishops only make this observation after investigating the Tome’s contents in order to verify correspondence with the orthodoxy of St. Cyril. The East will interpret this course of events not as if Peter intrinsically speaks through the Roman bishop, but rather as merely denoting that since Leo indeed teaches the truth, it is as if Peter, the infallible apostle himself, is now speaking through Leo. Conversely, the West will see in these proceedings at least seeds of papal infallibility mixed with the council’s political interest in demonstrating that the christology of Chalcedon in fact aligns with the Cyrillian theology articulated at Ephesus I as a result of the heterodox accusations that the empire had deviated on the matter.

• Chalcedon repeatedly underscores the necessity of the bishop’s conciliar and universal agreement, as well as somewhat paradoxically denoting papal prerogatives in determining orthodoxy:

“…This knowledge, descending to us like a golden chain by order of the Enactor, you have yourself preserved, being for all the interpreter of the voice of the blessed Peter, and bringing down on all the blessing of his faith. Wherefore we too, taking for our benefit you as our guide in the good, have displayed to the children of the church the inheritance of the truth; we have not given our instruction individually and in private, but have published our confession of the faith with a common spirit and with one accord and consent. We exulted together, delighting as at a royal banquet in the spiritual nourishment that Christ provided in your letter for those feasting, and we seemed to see the heavenly bridegroom sojourning with us. For if he said that ‘where two or three are gathered together in his name he is there in the midst of them,’ how close must be the fellowship he has exhibited in the case of five hundred priests, who gave priority to the knowledge of confessing him over homeland and exertion? Of these you were the leader, as the head of the members, exhibiting your prudence in those who represented you, while the faithful emperors guided them with a view to good order, as Zerubbabel did for Jeshua, in their eagerness to restore, like Jerusalem, the doctrinal fabric of the church.”

Price, Richard, and Michael Gaddis. The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon. p. 121

• As in the Ecumenical Council of Ephesus, Chalcedon lauds the Emperor as the “divine head” of the Church, the “new David,” and even a “priest,” once again underscoring the flowery nature of Byzantine language:

“The most glorious officials said: ‘Let the holy and ecumenical council say if it wishes the examination of this matter to be conducted according to the canons of the fathers or according to the divine mandates, concerning which we have already made known to all the pleasure of the divine head.’”

Price, Richard, and Michael Gaddis. The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon. p. 176

• Despite the adamant objections of Pope Leo and his legates, the 28th canon of Chalcedon officially continues the work of Constantinople I in elevating the Patriarchate of Constantinople to second in rank based on its imperial status, in contrast to apostolic lineage. As a result, Constantinople effectively becomes the court of appeals in the East.

• Pope Leo presciently predicts that the 28th canon, which Rome never ratifies throughout Church history despite eventually accepting the Patriarchal ordering contained therein, will cause the East to be reliant on imperial authorities instead of the divinely ordained head of the Church at Rome.

• 476 AD | Fall of Rome •

The Barbarians overrun Rome and leave the great city without an emperor for three centuries. The Pope, as a result, often becomes the de facto political head of the Western portion of Christendom.

• 484 AD | Acacian Schism •

The Acacian Schism between East and West commences as Eastern Emperor Zeno attempts to reconcile the monophysite faction within the empire by legislating an opaque definition of faith that seems to bypass the offensive theology of Chalcedon. This document, the Henotikon, results in a split with the Western Church and a temporary union with the monophysites.

• 495 AD | Decretal of Pope Gelasius I •

Pope Gelasius I defines that it is neither the councils nor canons which grant Rome primacy but rather the declaration of the Lord that he would build his Church on Peter which bestows on the Pope such authority. Accordingly, Gelasius further concludes that the Church of Rome has “neither spot nor wrinkle.” Some have claimed his Decretal is a forgery, however.

• 519 AD | Formula of Hormisdas •

Pope Hormisdas and Patriarch John of Constantinople eventually agree to end the Acacian Schim by discarding the tenets of the Henotikon and re-establishing communion through signing the Formula of Hormisdas which begins with an intense papal assertion:

“The first condition of salvation is to keep the norm of the true faith and in no way to deviate from the established doctrine of the Fathers. For it is impossible that the words of our Lord Jesus Christ, who said, “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my Church,” [Matthew 16:18], should not be verified. And their truth has been proved by the course of history, for in the Apostolic See the Catholic religion has always been kept unsullied.”

The Formula of Hormisdas.

However, Patriarch John comedically only signs the formula of reunion after revising its contents to indicate that the See of Peter entails both Rome and Constantinople.

• 553 AD | Fifth Ecumenical Council •

In another imperial attempt to reconcile the monophysite and dyophysite parties, Emperor Justinian posthumously condemns the Nestorian writings of clergy who Chalcedon had in fact restored to the episcopate. The impetus for the condemnations being that the monophysites had grown concerned that Chalcedon had simply been discrete Nestorianism and consequently Emperor Justinian sought to alleviate such notions in order to form a greater imperial alliance. As a result, the fifth Ecumenical Council of Constantinople II defines the dual nature of Christ with perhaps stronger theandric vocabulary than previously employed, while yet ultimately failing to unite the heretical monophysites to the orthodox.

• Constantinople II is entirely enveloped by imperial overreach, as Justinian attempts to overcome Pope Vigilius’ opposition to the posthumous condemnations. Consequently, Justinian wields the council against Vigilius in order to advance his imperial priorities.

• Pope Vigilius makes strong papal claims indeed comparable to the later definitions of Vatican I, and yet he appears to waver on his universally binding mandate. For, initially he ecumenically binds the Church to refraining from condemning the Nestorian writings, only to then later completely reverse his decision in the same unequivocal terms [see my “Fiat of Conversion” post for an explanation of the matter from a Catholic perspective].

• The council and Emperor retaliate against Vigilius’ initial opposition to the condemnations by in fact deposing the Pope himself. The bishops explicitly apply the Lord’s promise of indefectibility in Matthew 16:18 to the Church as a whole, in context implying that the gates of Hades had in contrast prevailed against Vigilius. Inexplicably, however, the council considers itself to still, in some respect, remain in union with the papal office in general, simply not the current claimant to the Roman See (Vigilius).

• Remarkably, despite the council’s actions, Vigilius and the West eventually come to recognize Constantinople II as ecumenically binding.

• 589 AD | Third Council of Toledo •

At the local Third Council of Toledo in 589, Visigothic Spain officially enters into union with the Catholic Church and accepts the Nicene-Constantipolitan Creed. In order to combat the Arian heresy prominent throughout the West, the synod seeks to stress the Son’s consubstantiality with the Father by notoriously inserting the Filioque into the Creed, resulting in its contents denoting that the Spirit “proceeds from the Father and the Son.”

The Filioque will be embraced by the entirety of the West but be opposed when eventually reaching the East. During this time period, the spurious Athanasian Creed circulates in the West with the Filioque clause included. The addition seems to first be confronted in the East in St. Maximus’ Letter to Marinus a few decades later.

• 590 AD | Ecumenical Bishop Dispute •

Pope St. Gregory the Great learns of the Patriarch of Constantinople’s title of “ecumenical bishop” and presupposes that the term “ecumenical” refers to an assumed universal jurisdiction in the Church. The reality being, however, that “ecumenical” merely refers to the Patriarch’s location in the Empire’s Capitol, but unaware of this common imperial designation, Pope Gregory characterizes the gravitas of the moniker as being “the forerunner to the antichrist.”

Ironically, later popes will claim to in fact be universal bishops, which is at least in a univocal sense the same title Pope Gregory lambasts, but perhaps not in substance, as some apologists claim he understands the title at the time to have implied that no other bishop exists in the Church.

• 640 AD | Letter to Marinus •

The great Eastern Saint Maximus the Confessor composes his Letter to Marinus in which he addresses the Latin usage of the Filioque and attempts to assure the East that the Romans are not Trinitarian heretics. His representation of the Western position is as follows:

“[The Latins] do not make the Son the cause of the Spirit, for they know that the Father is the one cause of the Son and the Spirit, the one by begetting and the other by procession, but they show the progression through him and thus the unity of the essence.”

St. Maximus, Letter to Marinus.

The East and West will debate the exact meaning of his perspective – as well as the actual authenticity of the letter – at the Council of Florence in the 15th century.

• 649 AD | Lateran Synod •

St. Maximus and Pope Martin I work in tandem to convoke the Lateran Synod in order to combat growing heretical offshoots of monophysitism, specifically monothelitism and monoenergism, which posit that Christ’s two natures combine to maintain either only one will or one energy respectively. These heresies overrun the Eastern Empire and force St. Maximus to take refuge in Rome from imperial persecution.

• Beyond St. Maximus himself, the synod enjoys no eastern participation, and it is even suspected that Maximus may have forged the entirety of the council’s proceedings.

• Regardless, the synod makes universal jurisdictional claims for the Pope and on the basis of Petrine authority excommunicates all those who deny the two wills and two energies of Christ. St. Maximus’ himself appears to maintain a strong papalism, undoubtedly encouraged by the refuge he found in the papacy, characterizing the bishop of Rome as the “sun of unfailing light… the sole base and foundation which cannot be overcome by the gates of Hades, according to the promise of the Savior.”

• Despite the synod’s own claims to ecumenicity, the East, and remarkably even the West itself to this day, never accepts the council as universally binding. Instead, the subsequent Council of Constantinople III will address the heresies of monothelitism and monoenergism and be considered ecumenical through garnering the participation and ratification of all Patriarchs (unlike the Lateran Synod).

• 681 AD | Sixth Ecumenical Council •

As imperial efforts to reunite the monophysite nations with the dyophysite Empire continue through the heretical halfway houses of monothelitism and monoenergism, the East again falls out of communion with the orthodox West which remains staunchly against any heretical concessions. Eventually, Emperor Constantine IV seeks reunion with the West and convenes the sixth Ecumenical Council of Constantinople III to theologically align both sides of the Empire.

• The entirety of the council’s Acts are not yet compiled, however, we know that Constantinople III implements the fullness of St. Maximus’ Christology, albeit without explicit appeal to the Saint for political reasons.

• Pope Agatho’s letter to the council included in the ratified Acts adamantly asserts that Christ will preserve the Roman See from error until the end of the age:

“…the Apostolic Church of Christ, has both in prosperity and in adversity always held and defended with energy; which, it will be proved, by the grace of Almighty God, has never erred from the path of the apostolic tradition, nor has she been depraved by yielding to heretical innovations, but from the beginning she has received the Christian faith from her founders, the princes of the Apostles of Christ, and remains undefiled unto the end, according to the divine promise of the Lord and Saviour himself, which he uttered in the holy Gospels to the prince of his disciples: saying, Peter, Peter, behold, Satan has desired to have you, that he might sift you as wheat; but I have prayed for you, that (your) faith fail not.”

The Letter of Agatho (Read at the Fourth Session), Council of Constantinople III.

• Similar to the case of Pope Leo at the Council of Chalcedon, the bishops seem to only accept the Pope’s letter, which explicates the duality of Christ’s wills and energies, after first verifying that its contents maintain orthodoxy. Whether these actions are mere political posturing or instead indicative of the contingency of papal orthodoxy, remains up for debate. Regardless, Pope Agatho’s letter undeniably denotes his own subscription to papal infallibility and importantly is enshrined in the official promulgation of the council’s Acts.

• Ironically, however, Constantinople III in conjunction with Pope Agatho anathematizes his predecessor, Pope Honorius, explicitly for the heresy of monothelitism. The West will defend this potential threat to papalism on two fronts: either Honorius never in fact espoused monothelitism and the council simply erred in a matter of fact (not faith), or he never magisterially bound the Church to a doctrinal position in his controversial letter [I find both plausible and internally coherent].

• 692 AD | Quinisext Council (Trullo) •

As the fifth and sixth ecumenical councils had inexplicably neglected to outline disciplinary canons, the Council of Trullo (or the Quinisext Council) of 692 attempts to supplement this past oversight. Although the East readily accepts Trullo as a binding addendum to the prior councils, the West never ratifies the synod’s canons. Indeed, many of the canons exhibit targeted criticism of Western customs and enshrine a significant growth in imperial prerogatives.

The council ratifies 85 of the Apostolic Canons, including most notably the 34th canon which underscores the importance of synergism between primate and synod. Moreover, it enshrines the Pentarchy of the Patriarchs, ranking them as Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and then Jerusalem. The West comes to officially accept this ordering in the Middle Ages.

• 749 AD | St. John of Damascus •

St. John of Damascus writes his summation of Catholic doctrine entitled “The Fount of Knowledge.” The Saint is most renowned for his defense of the veneration of icons based on the notion that the honor rebounds to the prototype depicted. Likewise, in his work, he denotes that the Church labels only the Father as “cause” in the Trinity, while granting that the Spirit originates “through” the Son.

“Further, it should be understood that we do not speak of the Father as derived from any one, but we speak of Him as the Father of the Son. And we do not speak of the Son as Cause or Father, but we speak of Him both as from the Father, and as the Son of the Father. And we speak likewise of the Holy Spirit as from the Father, and call Him the Spirit of the Father. And we do not speak of the Spirit as from the Son but yet we call Him the Spirit of the Son… And we confess that He is manifested and imparted to us through the Son… It is just the same as in the case of the sun from which come both the ray and the radiance (for the sun itself is the source of both the ray and the radiance), and it is through the ray that the radiance is imparted to us, and it is the radiance itself by which we are lightened and in which we participate. Further we do not speak of the Son of the Spirit, or of the Son as derived from the Spirit.”

St. John of Damascus, An Exposition of the Orthodox Faith (Book 1), Chapter 8.

In debates with the West, the East will repeatedly appeal to St. John’s perspective on the Trinity throughout Church history.

• 754 AD | False Council of Hieria •

Eastern Emperor Constantine V convenes the synod of Hieria, which purports to be ecumenical, in order to ban the veneration of icons. However, the false council receives no Patriarchal representation or ratification, yet its prohibitions are oppressively implemented by the Emperor. Interestingly, he still allows icons of himself to be venerated, perhaps betraying his nefarious motives to simply assert the State’s power over the Church.

• 787 AD | Seventh Ecumenical Council •

With a change in Eastern imperial dispositions, the seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea II is convened by Patriarch Tarasios of Constantinople at the behest of the Emperor and Empress in order to revoke the decisions of Hieria. Ultimately, Nicaea II dogmatizes the theology of St. John of Damascus regarding icons and even characterizes icon veneration as an apostolic practice.

• The Emperor and Empress invite Pope Hadrian I to attend the council, addressing him as the unique head of the Church, while stressing that the doctrinal debate should be resolved in a conciliar manner to avoid schism.

• During the proceedings, the Pope underscores his role as the distinct successor to Peter, unique vanguard of orthodoxy, and indicates that Peter will have a successor in his See until the end of the age.

• Concurrently, the bishops at Nicaea II reject the false council of Hieria on the basis that it failed to meet three specific criteria: 1) the cooperation of the Pope, 2) assent of the Patriarchs, 3) and the orthodoxy of the preceding ecumenical councils.

• Patriarch Tarasios potentially confesses a type of Filioque, as he espouses the phrase “through the Son” as a descriptor of the Spirit’s procession.

• While the West will historically treat the canons of ecumenical councils as more pliable and excommunications of persons as potentially fallible, Nicaea II characterizes the excommunications and canons of all ecumenical councils as specifically “divine” and “unshakable.”

• 800 AD | Coronation of Charlemagne •

Pope Leo III crowns Charlemagne, the King of the Franks, as the first Western Emperor since the fall of Rome in 476 AD. Accounts detail Charlemagne’s surprise at the Pope administering his coronation, implying the precedence of the Church over the State. The new reign of a rival emperor in Rome kicks off insurmountable political conflict between the East and the West.

• 863 AD | Photian Schism •

A four year schism between Rome and Constantinople commences, as the latter asserts its right to appoint its own patriarch without papal approval. Rome’s concern, however, regarding the appointment of Photios to the Patriarchate as a replacement to the reigning Ignatius is twofold: it reeks of pure imperial overreach into ecclesiastical matters and appears to circumvent canonical prescription as it requires fast-tracking the layman Photios through all Holy Orders in a single day.

Amidst the raging canonical dispute, Photios excommunicates Pope Nicholas, citing the Filioque as one of the Pope’s damnable errors, and produces his Mystagogy on the Holy Spirit to defend his position against the Filioque. He posits that the Filioque creates a dyad in the Trinity, as only one “cause” can be ascribed to the Persons if monotheism is to be preserved. For the rest of history, the East will continue to be unsure how exactly the West is employing the term “cause.”

• 869 AD | Ignatian Council •

The Ignatian Council (also known as the Council of Constantinople IV) is convened by the Eastern Emperor Basil I with the support of Pope Hadrian II in order to remediate the ongoing schism. Approximately only 12 bishops attend and eventually legates of dubious authenticity supposedly representing all Patriarchs ratify the synod, technically granting it ecumenical status. Photios is called before the council to testify regarding his non-canonical action of excommunicating Pope Nicholas, and his refusal to recant results in his own excommunication.

• The canons of the council explicitly indicate that a Pope is above a council and that he can be judged by no one, however, while also implying that judgment may be merited perhaps in the case of heresy.

• The West will retain this as the eighth ecumenical council, with the East ultimately rejecting it as binding.

• Hardly mentioned is the fact that the 21st canon of this council actually enshrines the Pentarchy, evidencing, finally, official Western acceptance of Constantinople’s second rank:

“And therefore we decree that no secular power should attempt to defame or remove from his See any of those who preside in the Patriarchal Sees, but they should consider them worthy of all respect and honour, pre-eminently the most holy pope of Elder Rome, secondly the Patriarch of Constantinople, and then those of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.”

Price, Richard, and Federico University. The Acts of the Council of Constantinople of 869-70. p. 407

• 879 AD | Photian Council •

Two years prior in 877 AD, Ignatius had died and Photios was once again appointed to the Patriarchate. Consequently, in 879 AD, Emperor Basil I convokes a council in Constantinople, often termed either the Photian Council or Constantinople IV, to garner official papal approval of the appointment. In contrast to the minuscule attendance at the Ignatian Council a decade earlier, the Photian Council hosts over 400 bishops and legates from all five Patriarchates.

• After laying aside the surrounding political issues, the anathemas against Photios put forth by the Ignatian Council are negated by this Photian Council with Pope John VIII’s approval.

• The synod anathematizes revisions to the Nicene-Constantipolitan Creed performed outside of a universal council based on the prohibition laid down at the Council of Ephesus, seemingly alluding to the West’s Filioque.

• It remains unclear to what extent Pope John VIII ratifies this council, beyond acceptance of the nullification of the anathemas against Photios (thus Photios dies in communion with Rome). For, the Pope will return to Rome and pastorally refrain from officially promulgating the Filioque in the Latin creed – however, there is never a posture in the West that the Filioque has indeed been condemned as heresy.

• The East typically considers the Photian Council of 879 to be the eighth ecumenical council in contrast to the Ignatian Council of 869 in the West.

The saga of the Photian Schism – albeit eventually healed – functions as a microcosm of the mounting political tensions between East and West which will ultimately culminate in the Great Schism.

• Great Schism Period •

NOTE: While the Schism has technically never ended, a notable shift in the overall tenor of the conversion between East and West took place in the 20th century. Prior to this, the second millennium unfortunately consisted primarily of speaking past each other and fomenting divorce.

• 1019 AD | Pope Struck from Diptychs •

The East ceases their recitation of the Roman bishop in the diptychs, denoting a rupture in communion. However, it appears that some theologians even at this time remain confused as to why communion has ended in the first place.

Yet, during this period, the Patriarch of Antioch and Constantinople correspond regarding the errors of the Latins, and explicitly highlight the Filioque as the central justification for the cessation of communion.

• 1054 AD | Mutual Excommunications •

Delegates of Rome and Constantinople officially excommunicate each other principally due to ongoing political tension in the Balkans. The reasons cited on both sides entail a number of marginal accusations, such as facial hair among clergy and the use of different bread in the Eucharist, with the principal theological rationale for the Schism being the insertion of the Filioque to the Creed. It is likely that nobody at the time considers this a significant, permanent rupture; yet, in reality, it marks the end of communion between East and West for at least nearly a millennium, officially ushering in the Great Schism.

• 1076 – 1124 AD | Investiture •

Throughout the 11th and 12th centuries, the Investiture Controversy plagues the Western Church, as the Papacy struggles to wrestle from the Emperor exclusive authority to appoint bishops. A significant growth in Papal claims occurs through the Gregorian reforms in order to counter this ongoing imperial interference.

The Ignatian Council of 869 is now officially considered ecumenical by Western canonists principally due to its stronger papal canons. Concurrently, the canonists completely forget about the existence of the subsequent Photian Council of 879 which had nullified the anathemas of Photios levied at the Ignatian Council of 869. As a result, Photios grows to be considered once again an arch-heretic in the Western mind, despite in reality having died in communion with Rome.

Surely without coincidence, during this time period the Donation of Constantine forgeries circulate throughout the West, providing the Church with new leverage against an encroaching imperium as the documents spuriously detail Constantine’s delegation of his temporal authority to the Pope.

• 1095 AD | First Crusade •

The First Crusade is launched by the West, in tandem with the East, to seize back the Holy Land from the intrusive Islamic Ottoman Empire. Multiple crusade campaigns will occur over the next two centuries – without lasting success.

• 1204 AD | Sack of Constantinople •

Rogue Latin crusaders sack and desecrate the city of Constantinople despite being occupied by Orthodox allies. Moroever, the Western Church establishes parallel Latin episcopates throughout the decimated Orthodox region. This event is often cited by historians as the turning point where the Schism became ingrained among the laity of the East.

• 1215 AD | Council of Lateran IV •

In 1215, at the Western Ecumenical Council of Lateran IV, the West elaborates on the Triadology of the Filioque, emphasizing the unity and simplicity of the divine essence:

“It is therefore clear that in being begotten the Son received the Father’s substance without it being diminished in any way, and thus the Father and the Son have the same substance. Thus the Father and the Son and also the holy Spirit proceeding from both are the same reality.”

Constitution 2, Council of Lateran IV.

In addition, this Council ratifies the traditional ordering of the Patriarchal Sees, while emphasizing their authority is contingent on communion with the Bishop of Rome:

“Renewing the ancient privileges of the patriarchal sees, we decree, with the approval of this sacred universal synod, that after the Roman church, which through the Lord’s disposition has a primacy of ordinary power over all other churches inasmuch as it is the mother and mistress of all Christ’s faithful, the church of Constantinople shall have the first place, the church of Alexandria the second place, the church of Antioch the third place, and the church of Jerusalem the fourth place, each maintaining its own rank. Thus after their pontiffs have received from the Roman pontiff the pallium, which is the sign of the fullness of the pontifical office, and have taken an oath of fidelity and obedience to him they may lawfully confer the pallium on their own suffragans, receiving from them for themselves canonical profession and for the Roman church the promise of obedience. They may have a standard of the Lord’s cross carried before them anywhere except in the city of Rome or wherever there is present the supreme pontiff or his legate wearing the insignia of the apostolic dignity. In all the provinces subject to their jurisdiction let appeal be made to them, when it is necessary, except for appeals made to the apostolic see, to which all must humbly defer.”

Constitution 5, Council of Lateran IV.

• 1270 AD | St. Aquinas’ Triadology •

St. Thomas Aquinas expounds on St. Augustine’s Triadology and becomes the de facto Western authority on the Trinity. In conformity with St. Augustine, St. Aquinas appeals largely to temporal analogies that establish the Son’s notional priority to the Spirit, implying his causality of the Spirit’s origin as a result of the simplicity of the divine substance.

• 1274 AD | Council of Lyons II •

The Council of Lyons II attempts to foster reunion between East and West while dogmatizing papal privileges and the Filioque:

“We profess faithfully and devotedly that the holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father and the Son, not as from two principles, but as from one principle; not by two spirations, but by one single spiration. This the holy Roman church, mother and mistress of all the faithful, has till now professed, preached and taught; this she firmly holds, preaches, professes and teaches; this is the unchangeable and true belief of the orthodox fathers and doctors, Latin and Greek alike. But because some, on account of ignorance of the said indisputable truth, have fallen into various errors, we, wishing to close the way to such errors, with the approval of the sacred council, condemn and reprove all who presume to deny that the holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father and the Son, or rashly to assert that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son as from two principles and not as from one.”

Constitution 2.1, Council of Lyons II.

While it receives imperial acceptance by the Eastern Emperor, it obtains no ecclesiastical participation or ratification by the Eastern Church itself. Lyons II is accordingly considered an ecumenical council only in the West today.

• 1285 AD | Council of Blachernae •

The Eastern Council of Blachernae is most likely convened in response to the Western Council of Lyons II and dogmatizes that the Spirit’s relation to the Son is one of energetic manifestation as opposed to the hypostatic origin of the Filioque:

“To the same, who affirm that the Paraclete, which is from the Frather, has its existence through the Son and from the Son, and who again propose as proof the phrase “the Spirit exists through the Son and from the Son.” In certain texts [of the Fathers], the phrase denotes the Spirit’s shining forth and manifestation. Indeed, the very Paraclete shines form and is manifest eternally through the Son, in the same way that light shines forth and is manifest through the intermediary of the sun’s rays; it further denotes the bestowing, giving, and sending of the Spirit to us. It does not, however, mean that it subsists through the Son and from the Son, and that it receives its being through Him and from Him. For this would mean that the Spirit has the Son as cause and source (exactly as it has the Father), not to say that it has its cause and source more so from the Son than from the Father; for it is said that that from which existence is derived likewise is believed to enrich the source and to be the cause of being. To those who believe and say such things, we pronounce the above resolution and judgment, we cut them off from the membership of the Orthodox, and we banish them from the flock of the Church of God.“

Canon 4, Council of Blachernae 1285.

Some Easterners, most notably Patriarch John Bekkos XI of Constantinople, find the distinction between “energetic manifestation” and “hypostatic origin” to be novelly contrived. However, the energetic manifestation paradigm grows to be the official Eastern position over time.

• 1330 AD | Palamas’ Theology •

Renowned Eastern bishop and saint Gregory Palamas articulates his perspective on the Filioque, echoing the position enshrined at the Council of Blachernae, while also explicating the essence-energy distinction. Palamas defends the Spirit’s relation to the Son as one of energetic manifestation, not hypostatic origin, in his Apodictic Treatises on the Procession of the Holy Spirit.

According to Palamas, although the Son is the Person who allows the Father to be termed Father in the first place, this notional priority of the Son to the Spirit does not result in the Son being a “cause” of the Spirit’s origin:

“The Holy Spirit, therefore, proceeds from the Father alone, exactly as the Son is begotten from the Father alone. And, according to His existence, He clings to the Father both directly and immediately, just like the Son, although it is through the Son that He acquired the power to be the Father’s Spirit, since the One causing procession is also a Father.“

Palamas, S. G. (2022). Apodictic treatises on the procession of the Holy Spirit. Uncut Mountain Press. pp. 101

Furthermore, in contrast to St. Aquinas in the West, Palamas argues the energies of the Spirit, and not his hypostasis, are given to the disciples by Christ, establishing a parallel for the eternal relations. Ironically, this implies Eastern theologians historically agree with the West that the temporal relations establish the eternal relations – despite all modern polemics against this reality.

[To me, it remains preposterous that the Son does not send the hypostasis of the Spirit – but I digress.]

• 1351 AD | Palamite Synods •

The Palamite Synods are held which dogmatize for the East the essence-energy distinction in God; specifically that, to some degree, God’s energies, or actions, are distinct from his essence. This understanding is often employed in differentiating between the energetic manifestation and the hypostatic origin of the Spirit.

The exact nature of the essence-energy distinction is of much debate, with Western theologians historically balking at the proposition out of concern that it produces accidents or parts within God. The East contends this is a misrepresentation of the distinction, and even modern Western scholars now tend to view the Eastern position as indeed compatible with Thomism. However, its application to the Trinitarian debates has not been embraced by the West.

• 1431 AD | Council of Florence •

From 1431-1449 AD, the attempted reunion Council of Florence is convened and ultimately fails to establish lasting communion between East and West. The council dogmatizes the supremacy of the Pope and defines the Filioque as meaning that the Father and Son are one cause of the Spirit’s hypostatic origin:

“…the Holy Spirit is eternally from the Father and the Son, and has his essence and his subsistent being from the Father together with the Son, and proceeds from both eternally as from one principle and a single spiration. We declare that when holy doctors and fathers say that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son, this bears the sense that thereby also the Son should be signified, according to the Greeks indeed as cause, and according to the Latins as principle of the subsistence of the Holy Spirit, just like the Father.”

Council of Florence, Session 6, July 6, 1439.

• Florence follows on the heels of the Western Schism, in which three rival claimants to the Papal See were only sorted out by the convening of the Council of Constance – damaging optics to the notion that the Papacy remains above the judgment of a council. Resoundingly, Pope Eugene IV leverage Florences to bolster any threatened papal claims, reinforcing that the Pope is the head of the Church, the Vicar of Christ, successor of Peter, and retains universal jurisdiction over all bishops.

• Strong statements are made concerning the inability to obtain salvation outside the Roman communion, which will later come into tension with the arguably more accommodating soteriology articulated at Vatican II.

• St. John of Damascus is cited by the East as the central patristic figure against the Filioque, with St. Maximus’ position in his Letter to Marinus being proposed as a unifying theology. Yet, ultimately, the idea is rejected by both Rome and the Eastern delegate Mark of Ephesus due to each side’s inability to agree on the exact meaning of the patristic term “cause.”