Although much more could be discussed regarding these doctrinal disputes between Protestantism and the Catholic-Orthodox perspective, I have chosen to highlight the issues that I believe cut to the conceptual differences between both camps and ultimately fundamentally justify the “Cathodox” position. For the sake of brevity, I have included an “In Brief” response to each Misconception in case the reader would prefer to save time rather than digesting the entirety of the “Full Response.”

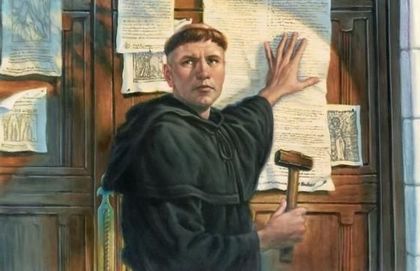

While Luther pounded on the door, St. Peter held the keys.

• Preface •

Among theologians, a common distinction is proposed between the terms “eisegesis” and “exegesis” – the former being the act of imposing the reader’s own interpretation onto a text, while the latter supposedly being the act of accurately extracting the text’s unfiltered meaning. Doctrinal opponents will routinely lambast each other for performing “eisegesis” when they disagree regarding the interpretation of Scripture. The superfluous nature of this distinction is evident when one considers that no reader would propose that his interpretation is contrary to the true meaning of the text, rather, of course, every single theologian in history believes himself to be performing “exegesis” (i.e., interpreting that which Scripture is in fact communicating). In my experience, this pejorative distinction subsists most frequently in Protestant circles where nominalism maintains a stronghold, resulting in the notion that purely accidents are determinative of meaning. Consequently, their theologians – perhaps, unconsciously – tend to underestimate the breadth of meaning a single word can possess depending upon its contextual usage, as the underlying assumption is that a word’s textual meaning is intrinsically evident due to its accidents. The Reformation’s doctrine of the “perspicuity of Scripture” is a manifestation of this perspective, as it posits that Scripture is sufficiently clear in its essential matters and thus the “exegesis” of passages should be fairly straightforward. In contrast, St. Peter emphasizes that St. Paul’s writings are difficult to understand and as a result many incorrectly interpret them to their own destruction: “As also in all his epistles, speaking in them of these things; in which are certain things hard to be understood, which the unlearned and unstable wrest, as they do also the other scriptures, to their own destruction” (2 Peter 3:16). Ironically, the point upon which Scripture seems to be the most clear is that it is in fact unclear, and left to one’s own interpretation, an individual can fall into damnation.

I highlight the interpretive difficulties that naturally occur within the Biblical text as an example of how a nuanced and diligent clarification of terms is vital to the productive analysis of worldviews in general – lest we fall into destruction. Today, in the United States, Protestantism reigns culturally supreme, resulting in the vocabulary and practices of Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy being unintelligible at best and scandalous at worst to the common layman in this country. On the surface, the terminology and customs of these apostolic communions may even reek of pagan syncretism and Judaizing tendencies from the Protestant’s perspective, if not properly clarified. Words have taken on such subtle yet widely divergent meanings in both camps that a diligent dissection of their undergirding paradigms is paramount for any theological progress to be achieved. A basic example of this phenomenon is the archaic usage of the word “worship,” as the term’s broader definition in antiquity encompassed the idea of mere reverence. Accordingly, older Catholic documents will undoubtedly horrify the unfamiliar Protestant reader when their texts commend “worship” of Mary and the Saints, if it is not realized that this is simply an endorsement of reverence – not an encouragement of “worship” in the narrow modern sense that is due to God alone. This is an instance that remains relatively surface level, but the issues only compound the deeper one investigates as the paradigms arguably diverge over concepts as foundational as person and nature, leading to insurmountable subconscious gulfs undergirding all other areas of theology. While the nuance of the ancient Christian religions at first blush risks coming across as nauseating sophistry, the millennia of combat against manifold heresies has forced the apostolic Churches to minutely and legitimately refine their terminology to accord with orthodoxy. In my own journey, it took several years of inculturation before I could even begin to understand the philosophical framework underpinning Catholicism – and only then could I apprehend the actual terms themselves. I am the beneficiary of being thrust into a theologically foreign environment for nearly five years through my employment, growing in acceptance of the shocking reality of my own theological error, and then frantically consulting clergy and thousands of Church documents for another three years (and counting) to reconstruct my beliefs. In that vein, with the hopes of advancing ecumenical dialogue, I would like to offer assistance in clarifying 10 misconceptions regarding Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy that I myself once assumed and which also seem to be the most pervasive within Protestantism. Reciprocally, this discussion may likewise serve to enlighten the Catholic or Orthodox reader as to why Protestants are often so utterly appalled by that which they consider, albeit erroneously, to be the Catholic and Orthodox (“Cathodox”) religion.

• Theological Context •

Many of the misconceptions require extensive examination in order to fully grasp the Cathodox position; nevertheless, this blog entry will simply attempt to provide a succinct elucidation of the topics that can serve, perhaps, as a catalyst for more thorough investigation elsewhere. Before addressing the misunderstandings head on, a brief treatment of the underpinnings of apostolic theology is required so as to contextualize the specific Cathodox doctrines. Firstly, many strains of Protestantism tend towards a Platonic, if not gnostic, understanding of soteriology, in which the primary telos of salvation is escaping this fallen world in order to dwell in a transcendent heaven. The great chasm between heaven and earth only grows as one traces the lineage of Protestantism from the initiators of the movement, Anglicanism and Lutheranism, down to the modern ecclesiastical communities that identify as non-denominational: the gap between the two worlds continuing to widen as one progresses along the timeline of Protestant history. This great divorce between the heavenly, or the spiritual, and the earthly, or the physical, comes with a bevy of theological implications. For instance, the dichotomy undercuts God’s ability to use material means for spiritual ends (such as sacraments), relegates our redemption to a notional declaration by God of our righteousness without Christ’s righteousness taking any immanent effect within our ontological being, and ultimately discards this world as superfluous to man’s eternal state. Conversely, the Cathodox soteriology is one of marriage and redemption – not divorce and escapism. When Christ prophesied that this world would be subjected to fire and that a new heaven and new earth would be fashioned, he in fact taught a doctrine of purification, not of annihilation. For, is a man annihilated when he is saved? Or does not that same man continue to exist, and yet subsist as a “new,” or renewed, man after Christ saves him? Paul writes that many will be “saved as through fire,” denoting their purification, not their destruction; for how can one be characterized as saved if he is indeed destroyed? In the same manner, so will Christ bring fire upon this world in order to purify and renew it – a baptism by fire that preserves and sanctifies the world. This purification of the world is ushered in by the marriage of heaven and earth through Christ’s Body: when the Second Divine Person of the Trinity incarnated into physical, human nature, he brought the heavenly and earthly realms into intimate union. Christ then conquered death through his resurrection and ascension, simultaneously resurrecting and ascending the world into the Holy of Holies in Heaven as its High Priest through his sharing of the material nature of this world. His Church, by virtue of being his literal and sacramental resurrected Body, enjoys a foretaste of this consummated union and is tasked with the propagation of this ascended existence throughout the entire world. For, God has descended to our world, not to annihilate it, but so that it might then ascend with him into a deified state for all eternity.

Accordingly, mankind’s salvation is not a notional, judicial declaration by God of our righteousness without immanent effect, rather it is a literal transformation, more properly, a deification of our entire human nature through the indwelling of the Divine Spirit which imbues our very being with the righteousness of Christ: we are made righteous, not merely considered righteous. This is the true essence of justification: transformation, regeneration, and renewal through adoption into divine sonship, for, “You are gods, and all of you are children of the Most High” (Psalms 82:6). With the spiritual and physical worlds united through Christ’s Body, material means (sacraments) located in the divine-human sphere of the Church are not opposed to spiritual ends but are in reality intimately ordered towards spiritual ends, as the Holy Spirit rests in the physical sacraments as he eternally rests in Christ (just as a human spirit rests in a human body) since the Church is Christ. The sacraments of the Church are not equivalent to the works (or rituals) of the Old Testament Law, which were not conducive to divine sonship since they lacked intimate union with Christ and his Spirit, but instead the sacraments are works (or rituals) that have been infused with the Spirit and therefore unite us to Christ’s literal, sacramental Body in order to incorporate us into the sonship of Christ. In his Epistles, Paul did not condemn “works” in general as a means of salvation, but referenced specifically the Works of the Old Testament Law as inadequate due to their non-sacramental nature as they had not been infused with the Spirit in the same manner as the New Testament “works” and consequently could not impart divine sonship. Yet, these New Testament sacraments certainly mirror the Old Testament rituals in the manner of their shape and structure, for Christ specifically delineated that he came not to abolish the Law but to fulfill it. The Greek word for “fulfill” denotes the act of filling a vessel with a liquid – not of destroying the vessel – echoing the nature of Christ’s first miracle at the wedding in Cana whereby he transubstantiated into wine the water contained inside the jars used for Old Testament purification rites. Correspondingly, the New Testament takes on the shape of the Old Testament, but it contains and imparts something greater: adoption into the sonship that Christ has eternally enjoyed with the Father through the sacraments of Christ’s Church imbued with the Holy Spirit. It is important to clarify that God is indeed the ultimate cause of our salvation, while the sacraments are simply (to use Aristotelian terminology) instrumental causes – this being analogous to a chef who uses an oven to bake a cake, in that while the chef is the ultimate cause of the cake, he causes the cake to exist through the instrumental cause of an oven. Protestants likewise acknowledge at least the principle of instrumental causes to the extent that they affirm the instrumental cause of Scripture for man’s salvation, but often they fail to then extrapolate this principle to other areas of theology. Whereas, in the Cathodox paradigm, God works through instrumental causes in all areas: Scripture, angels, Saints, Mary, sacraments, priests, prayer, and ultimately his Son, without diminishing his own glory. Graciously, in the New Covenant, Christ has united heaven and earth in order to gift us sacramental instrumental causes for our redemption which fulfill the shadows of the Old Covenant – but it is our responsibility to choose to partake of them in order to transform our nature and truly be saved. These principles undergird the entirety of Cathodox theology and should be held in mind when addressing the 10 most common misconceptions below.

• Misconception #1 •

“Constantine created the Cathodox Church, as a synchronization of paganism with the pure Christian religion that existed prior.”

In Brief: Constantine’s convocation of the Council of Nicaea was compelled by universal doctrinal unrest over the question of Christ’s divinity and it subsequently defined that Christ shares full divinity with the Father. The Council defined no further dogmatic matters and merely established administrative protocols. Consequently, it cannot be characterized as a synchronization of pagan practices with Christianity. Likewise, if one were to posit that the Cathodox incorporated paganism in the successive centuries, the massive corpus of writings from the Church Fathers that remains accessible today, as well as the doctrinal unity across sizable ancient communions that developed separately, proves otherwise.

Full Response: While this is a common motif among many lay-people, no reputable scholar or historian would support this claim regarding Constantine. Frankly, it is a slander of so little substance that it is almost comical to address. To be clear, that is not a commentary on the individuals levying the accusation, but rather a note on the claim’s complete incongruity with the historical record. The accusation often goes that after Constantine legalized Christianity early in the 4th century, he convened the Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325 AD to meld his sun-worshiping pagan religion with Christianity. The peddlers of this theory typically propose that this is the moment when Cathodox practices of saint veneration, the Eucharist, priests, and many other doctrines were introduced into Christianity. The details surrounding the Council of Nicaea aptly reveal the cognitive dissonance required of this thesis. The reason for the council’s convocation was in fact that Christians around the world were divided on the issue of Christ’s divinity – specifically, whether Christ is of equal divinity with the Father. Archbishop Alexander of Alexandria was a theologian of the time who defended the doctrine that Christ is indeed of equal divinity with the Father and his orthodox adherents were widely persecuted by the opposing heterodox clergy. The debate sparked such disarray throughout the Roman Empire that Emperor Constantine pushed the Church to convene the first world-wide council in order to settle the matter. Nicaea subsequently defined that Christ is truly of equal divinity with the Father, adopting Archbishop Alexander’s position. Here’s the kicker: besides various minor administrative and canonical protocols, this remains arguably the sole theological issue addressed by Nicaea. There was no decision by Constantine to implement new doctrines or create new offices within the Church – no biblical canon was adopted, saints were not discussed, nor was transubstantiation defined. The reality is that many of these Cathodox beliefs were at most noted in passing, if at all, because they were already taken for granted as being true since they were the universal practice of the early Church prior to Nicaea. This is aptly demonstrated by the myriad of writings retained from the Church Fathers throughout the first three centuries prior to the council (Protestants are often completely unaware of the preservation of this vast corpus of writings, as the propagandized narrative is that history went virtually dark after the apostles and failed to resurface until the printing press 1500 years later). Instead, Nicaea simply defined Christ’s divinity – it offered virtually no further dogmatic insights. In fact, Alexander himself was a bishop before the council even convened, illustrating the ludicrous nature of some of these theories regarding Constantine’s establishment of the office of bishop or other Cathodox practices. If one were to blame Constantine and the Council of Nicaea for the invention of syncretic beliefs, arguably Christ’s divinity must likewise be rejected – since this was in reality the only doctrine Constantine and the council established.

Now, perhaps the reader readily agrees that the Constantine conspiracy holds no water but remains concerned that the Cathodox religion nevertheless integrated pagan practices over subsequent centuries, culminating in rank syncretism by the medieval period. Parallels between Cathodox and pagan practices may be cited as evidence, such as the devotion to saints superficially resembling pagan prayer to ancestors, a shared hierarchical structure, or a ritualistic worship service. Firstly, I would posit that the overwhelming majority of these practices find full expression in the earliest days of the Church, as documented in the hundreds of thousands of pages we possess from that time period (for roughly $3.00 on Amazon Kindle you can purchase approximately 400,000 pages of the Church Fathers’ writings). Moreover, any Cathodox beliefs not explicitly enumerated in the early Church, and they are few, are legitimate flowerings of their seed-form explicitly discussed in the Fathers and should not be impulsively discarded without consideration of legitimate development. This is illustrated by the fact that the Churches which broke off from the Catholic and Orthodox Churches in 431 AD and 451 AD retain the overwhelming bulk of these supposedly syncretic practices despite not developing alongside each other for the last 1500 years – including prayer to saints, transubstantiation, priests and bishops, liturgical worship, sacraments, Marian devotion, and the list goes on. One would have to propose that at least four sizable ancient Church communions (the Catholic Churches, the Eastern Orthodox Churches, the Non-Chalcedonian Churches, and the Assyrian Church of the East) all developed the same exact syncretic practices simultaneously despite not being in communion with each other for over a millennium, residing in distinct regions of the world, and indeed while viewing each other as heretical communions for reasons outside their shared beliefs. Now, the real reason for some level of similarity between the Cathodox Church and pagan religions is that Christianity is not a total annihilation of humanity and the world’s nature but rather its preservation, correction, and elevation. It is a working with and redeeming of this nature. The pagans produced practices that were nearly in line with human nature – but were diabolically corrupted by Satan and his demons. For, Satan does not totally alter the good beyond recognition, instead he peddles a cheap copy of the good in order to deceive mankind. Thus, for example, Satan is not a horned goat with a pitchfork, rather Scripture reveals he parades around as an angel of light. Likewise, the similarity between the Cathodox religion and the pagans indeed only underscores the veracity of the Cathodox position, as Satan has produced false copies within paganism in order to deceive the heathens. The fact that Protestantism is completely divorced from the natural human impulse, as well as Satan’s attempts at a mirage of truth, demonstrates it remains impotent to such a degree that Satan has exerted almost no effort emulating it in order to deceive the masses.

• Misconception #2 •

“The Cathodox uphold the Old Law as still in effect.”

In Brief: The Cathodox maintain that the New Covenant is a preservation of the shape and structure, but nevertheless an elevation, of the Old Covenant. For, as a shadow maintains the same outline of a person, the actual individual is a fuller picture of this outline. Likewise, the New Covenant fulfills and does not abolish the Old (as Christ himself states), while imparting greater promises in its sacraments: specifically, the privilege of participating in divine-human union. The Old Testament prepared the Israelites for this Covenant but remained incapable of imparting such salvation, as the Spirit did not imbue its works in the same manner as the New Covenant structure or sacraments.

Full Response: As mentioned in the introduction, the Cathodox understanding of the New Covenant is not a radical departure from the Old Covenant, nor is it a total retention, but rather an elevation of the prior covenant to one of divine sonship through the deification imparted by the Spirit. The New Covenant and Old Covenant are akin to two parallel lines, but with the New being higher on the y-axis than the Old. Consequently, it preserves a similar form to the Old Covenant, while offering higher, better promises – particularly adoption into divine sonship. In contrast, the pervasive Protestant notion of the Covenants is that they are two perpendicular lines, diametrically opposed to each other and accordingly assume radically divergent forms in order to deliver opposed promises. The Protestant paradigm results in God having taught the Israelites “what not to do” for millennia instead of pedagogically revealing the shadows of Christ so that they could be prepared to recognize and accept his full form when he appeared. The latter is the Cathodox perspective and underscores why the Jews had no excuse for their hard-hearted rejection of the Messiah: they knew who he was because they had been prepared by God to recognize him as the fulfillment of the Old Testament types, not as a completely radical divergence from that which they had already been taught. This preservation of the same shape of the Old Covenant in the New Covenant by the Cathodox, much like how an individual maintains the same form of his shadow while yet being the fullness thereof, often scandalizes the Protestants since their own complete rejection of the Old Testament types results in the Cathodox seeming too Jewish. In reaction to the mainstream Protestant rejection of continuity between the two covenants, a Hebrew Roots movement has emerged and over-corrected by preaching, like the real Judaizers, that it is necessary to abide by the precepts of the Old Covenant. However, the fault in this converse position is that the Old Covenant was meant to pedagogically prepare the Israelites for the fullness that was to come, and thus in and of itself the Old Covenant’s works could not offer true salvation – that is, adoption into divine sonship. This was Paul’s point in Romans and Galatians when discussing circumcision: it was a shadow that was meant to prepare the Israelites for the fullness thereof, and thus the ritual itself could impart no ontologically deifying effect. Circumcision, and implicitly all other works of the Old Covenant, could only dispose the adherent to recognize and receive the New Testament works, the sacraments, which are the only means of ontological transformation and salvation. Therefore, to continue the practice of circumcision, and the entirety of Old Testament works, for salvific purposes is to reject the uniquely salvific nature of the New Testament sacraments and forfeit redemption in total. While the Protestants abandon the deifying sacraments of the New Covenant because they appear too congruent with the Old Testament types, the Hebrew Roots movement rejects the deifying sacraments because they are not the exact same Old Testament practices. The Cathodox position takes the middle, narrow path that leads to eternal life: a fulfillment of the Old Testament types that parallels their form while imparting divine life through a new infusion of the Holy Spirit. Consequently, the New Covenant, in Cathodoxy, correctly mirrors the Old Testament in all aspects: a trifold clergy, a liturgical worship structure as seen in heaven by Moses and John, a new manna and a new Day of Atonement sacrifice in the Eucharist, a new immaculately designed Ark of the Covenant and Queen of the Kingdom in Mary, a new holy day of the week on Sunday, a new initiation into the covenant for infants through baptism that supersedes the old initiation of circumcision, a new Israel and thus certain mortal sins resulting in expulsion from the new kingdom of the Church, new keys to the kingdom being delivered to a new steward in Peter and his successors, new magisterial Mosaic authority to bind and loose laws and sins being granted to the apostles and their successors, and ultimately a new Moses and Angel of the Lord who delivers his people into the new Promised Land in Jesus Christ. Yet, while all these theological realities are parallels of their shadows in the Old Covenant, they elevate these shadows to a heightened mode of existence and uniquely offer a participation in the divine life which the Old Covenant was impotent to deliver.

• Misconception #3 •

“Cathodox believe ‘works’ earn you heaven.”

In Brief: Christ has united the material world with the supernatural realm, and consequently the material-divine hybrid means of salvation found within the Church, namely the sacraments, facilitate participation in the divine-human mode of existence ushered in by Christ’s incarnation. These instrumental causes of salvation are graciously offered to man by God and humanity has done nothing to merit their availability, however, now that they have been graciously offered, it is incumbent upon man to synergize with the sacraments. Through participating in these means of salvation, God does not simply notionally consider man righteous but literally alters his nature to be put into right order and enter a deified mode of existence. Whereas Adam passed down to his descendants a corrupted nature, the New Adam imparts to his brothers and sisters a deified mode of existence for those baptized into his lineage. This is what the Scripture means by salvation coming through “Christ’s righteousness” – his rightly ordered and deified human nature is imparted to those who have been united to him, rescuing those who have been baptized from eternal death and instead granting them a nature that eternally lives.

Full Response: The Cathodox are often caricatured as promulgating the notion that grace is unnecessary for salvation and that man can earn heaven on his own merits. In reality, this is the heresy of Pelagianism explicitly condemned by the Cathodox Church as early as the 5th century and conversely the Cathodox have always upheld the primacy of grace in man’s attaining to both faith and works, as left to his own devices he would exhibit neither of these virtues and be forever barred from heaven. Yet, the Protestant and Cathodox understanding of “works” and “faith” fundamentally diverge due to the chasm between God and this world created within Protestantism. As noted in the preface, through his incarnation Christ has intimately united the divine with the material, and then through his bodily ascension into heaven, he has moreover brought the entirety of the bodily world into a deified mode of existence as the High Priest of the entire creation. Salvation in the Cathodox paradigm then is an entering into this deified mode of existence of which Adam and Eve had a foretaste but ultimately lost. The Church is the new Garden of Eden in which the new Adam has ushered in a restored deified existence that the Old Adam forfeited. The new brothers and sisters of the new Adam participate in this deified mode of existence, as, with all siblings, they share to a degree in the same nature. Consequently, Cathodox soteriology is a question of how does one literally, not metaphorically, enter into this deified-human family enshrined by Christ in order to eternally live? The answer is that through the supernaturally deified material instruments, the sacraments, filled with the power of the Spirit one can be initiated into this divine-human family. When one is naturally conceived in his mother’s womb, he receives not a mere judicial designation of guilt from God due to Adam’s sin, rather he receives the same exact human nature of Adam as his descendent. This nature has been corrupted as a result of Adam’s sin, resulting in a mode of existence ordered towards sin and death instead of righteousness and life. This is the state of all of mankind’s nature when naturally conceived, yet when born again in the water of the Church’s womb through baptism, the initiate’s nature is changed back to the orientation of Adam in the garden whereby he is ordered towards goodness and union with God which imparts life. Accordingly, salvation is not the story of God arbitrarily designating eternal destinations through judicial judgments divorced from the ontological status of individuals, instead it is God’s actual remediation of our corrupted nature and elevation of it with Christ into a deified mode of existence through incorporation into the supernatural bloodline of the new Adam. This is in fact what Scripture means when it reveals we are saved by “Christ’s righteousness” – not that his works are notionally considered by God to be our own and thus merit us heaven, but that his rightly ordered nature (the true definition of right-eousness) becomes our own through sacramental union with him as the new Adam. Therefore, the biblical term “justification” denotes not a non-ontological imputation of Christ’s “merit” to the account of the believer, but rather a putting into right order the believer’s nature. Analogously, to “justify a paragraph” means to align its sentences into a uniform order which tangibly alters the nature of the paragraph – it does not simply change the writer’s notional consideration of the paragraph without effect on the nature of the paragraph itself. In the same manner, through sacramental union with Christ, man is justified, having his nature aligned towards life and no longer ordered towards death. In turn, “sanctification” is a growth in this right order, or “justification,” through yielding more and more to participation in this deified mode of existence. This is reflected in the incarnation, otherwise the incarnation becomes a purely superfluous venture by God, for the divine Christ took on human nature so that man himself might correspondingly obtain participation in the divine. As a result, while dwelling on this earth, we are graciously presented the opportunity to grow in participation in this deified mode of existence through the God-ordained means of the sacraments and the cultivation of charity in our souls. Conversely, like Adam and Eve, it remains within our capacity to also wane in our participation in the divine-human mode of existence and to ultimately entirely forfeit this gift by giving our soul over to sinful passions which alter our ontological status and orient us back to death. The degree to which we achieve participation in this divine-human union while in this life will determine our eternal mode of subsistence in the next life. This is why Scripture indicates that at the Great Judgment individuals will be held accountable for their deeds, as their works determine the degree to which they share in the divine-human mode of existence for all eternity.

With this framework as context, it is evident that the question “can you earn heaven?” normally derives from a competing Protestant paradigm that fails to incorporate the ontological aspects of salvation, resulting in the question being fundamentally misplaced. The Cathodox response is that there is indeed nothing one can do in order to deserve a deified mode of existence (heaven) in the strict sense, as the opportunity to enter into this salvific state is offered to mankind purely out of God’s unmerited grace. Yet, the reality of the situation is that God has indeed offered man this opportunity and it is his responsibility to respond by submitting to the means God has established in order to obtain this deified mode of existence – and if the Christian properly does so then he will be saved, but the onus remains on man to participate in the means established by Christ. In the end, the Cathodox position never posits that the works of man make him deserving of the opportunity to obtain a divine-human mode of existence, but rather that God has graciously provided a means of salvation with man’s works – specifically, through the sacraments and cultivation of charity – being either a growth or diminishment in this divine-human mode of existence enshrined by Christ’s incarnation. In fact, even the very impulse itself to partake of these salvific sacraments originates in God who graciously imparts the desire to the Christian, confirming the primacy of grace within Cathodoxy. Nonetheless, perhaps the Protestant is left wondering: “but of what is faith in this paradigm?” To juxtapose faith and works would be to divide a part from the whole, for faith is the conviction that Christ has been truthful regarding the works he has prescribed for redemption – it is the first step in participating in salvation. Similarly, if one has the goal of arriving at a destination, he must first possess faith in the map’s coordinates. Yet, simply trusting in the map’s veracity is not sufficient to arrive at the desired location, instead it is the first step in then following the map’s coordinates to the desired destination. In the same vein, “faith in Christ” is trusting that the works and instrumental causes that he has ordained for his people are in fact the correct means of transforming human nature and participating in a divine-human mode of existence. But merely believing Christ is telling the truth regarding the “coordinates to salvation” does not in fact “get you to the destination” of a redeemed nature – instead it is the actual entering into union with him through the prescribed means of salvation that “gets you to the destination” of redemption. The epic of Noah exemplifies this relation between faith and works, as Noah had faith, or trust, that God was being truthful when he revealed there would be a flood and the only means of survival was in fact a boat built according to the divine instructions. However, if Noah merely had faith, or trust, that God was being truthful and failed to in reality build the boat, he would not have achieved salvation, rather he would have drowned in the waters like the rest of the world. Accordingly, faith is the conviction that Christ has indeed established the means of salvation, which is itself an impulse graciously imparted by God, but man must then do the work of analogously building the Ark through entering into sacramental union with the Divine if he is to be saved from the floods of this world.

• Misconception #4 •

“The Cathodox believe in Tradition, which is merely a game of ‘phone-tag’ that communicates extra-biblical practices.”

In Brief: The Cathodox understanding of “Tradition” is not simply an oral passing down of non-biblical principles, but rather includes Scripture itself, as Tradition is the entirety of God’s revelation to man. As the Church itself precedes the Scriptures, and in fact composed and compiled them, the divorce of Scripture from the category of “Tradition” renders Scripture null as it in actuality exists within this category itself.

Full Response: A common refrain in Protestantism when enumerating divinely appointed authority is Sola Scriptura – albeit often carrying with it a wide range of meanings depending upon which Protestant is consulted – that is, “Scripture alone.” Regardless of the exact definition of this mantra presented, all Protestants will agree that it expresses a contrasting understanding of authority to that of the Cathodox who believe not in “Scripture alone” but in “Scripture and Tradition.” This particular conversation inevitably achieves no progress, as the two parties subconsciously maintain a radically different definition of “Tradition.” To the Protestant mind, “tradition” intrinsically denotes practices not explicitly commanded in Scripture but which have developed over time in particular cultures and are gradually integrated into various churches. Examples of such “traditions” are pews, styles of congregational music, architecture, etc. The Cathodox would affirm that this is its own subset of negotiable “tradition” but would never assert that this level of “tradition” rises to the status of authoritatively binding teaching – that is, capital T “Tradition.” Before examining the fullness of the Cathodox perspective, the two parties’ respective epistemologies need to be analyzed. In the Protestant paradigm, all binding theological knowledge must be rooted in explicit Scriptural passages. It treats the Scriptures more along the lines of legal precedent that outlines all doctrinal beliefs to the fullness that can be binding – and any attempts to go beyond the Scripture’s, so called, “explicit meaning” cannot be viewed as binding but only as personal conviction or “tradition.” Thus, without the Scripture, there would be no Christianity, for the Christian could not be bound to any dogmatic belief. Here we arrive at an insurmountable problem for the Protestant: where was the Scripture when the Church was founded at Pentecost and the subsequent decades? Perhaps, they answer: “Ah! But they possessed the Old Testament Scriptures!” Was it then true that only the Old Testament was binding for the first century Church? This is a manifestly ridiculous proposition to all Christians as Christ and the apostles had orally instructed the early Christians in the ways of the New Covenant, yet it is where the Protestant epistemology inevitably leads. Likewise, was Abraham bound to no theological framework as he preceded Moses’ Torah? What about Noah? Or perhaps Adam and Eve were not truly culpable for their violation of God’s covenant since it had not been written down in Scripture for them to exegete? Now we readily begin to see the inconsistency of this epistemology and it raises the questions: what exactly is Scripture and what is its relation to the oral revelation of God? The Cathodox answer is that Scripture itself can be viewed as a category within the Venn-Diagram circle of authoritative “Tradition” – not to be confused with non-authoritative customs or “traditions.” Scripture is arguably the highest authority within the authority of Tradition, but it is not itself a distinct aspect that is separate from the whole, rather it is the pinnacle of the whole. However, being intrinsically located within the whole of Tradition, if Scripture were separate from Tradition it would then lose all of its import. Thus, we begin to see a picture emerging of what exactly “Tradition” means to the Cathodox. Theological realities, as well as simply all of reality itself, are not dictated by Scripture but rather documented infallibly by Scripture. It is important that the cart is not put before the horse. Accordingly, in the Cathodox epistemology all of Christianity would still remain intact and be possible to observe even if the Scriptures never existed – as it is the Church, divinely and infallibly inspired by God as the bulwark of truth, that has produced the Scriptures – not the other way around – and preserves the truths of reality. For, in the formation of the Old and New Testaments, God’s people were initiated into a covenant and then while already participating in the covenant, Israel or the Church subsequently formulated the Scriptures. The Scriptures did not form God’s people, but rather God formulated the Scriptures through his already existent covenant people. As a result, the Scriptures themselves are authoritative “Tradition” preserved by the Church.

Now, just as the people of God have been tasked with the composition and preservation of this pinnacle of Tradition (the Scriptures), so too have they been tasked with the preservation of the Scripture’s meaning. The meaning of Scripture is the rest of the whole, of which Scripture is merely another part inside the Venn-Diagram circle of Tradition. Accordingly, the full meaning of the Scriptures have been preserved in the magisterial definitions and universal practices of the infallible Church since the time of Christ. In fact, the practices preceded the Scriptures! To separate the ancient “Traditional” practices and interpretations from the Scripture is to completely decontextualize the Scripture and strip it of all meaning. The Protestant reader then simply maps his own cultural biases onto the text, forming a religion of his own making, as he has no divinely guided Church to impart the Traditional understanding of the Scriptures. Conversely, the ancient belief universally held among all Christians prior to the Reformation was that God designated a specific Church to infallibly retain the whole of the Christian Tradition: which includes Scripture, its meaning, and its implementation. That which the one divinely ordained Church has defined for the last 2,000 years, including Scripture and the whole of its meaning, is what the Cathodox mean by “Tradition.” If Scripture is authoritative, then this “Tradition” by necessity must likewise be authoritative as it precedes, creates, and includes the Scripture. Perhaps the Protestant may retort: “but which Church is the one, infallible Tradition?” Unfortunately, Sola Scriptura fails to allow the Protestant himself to escape this epistemological dilemma, as he must confront a similar question: “which biblical canon is the one, infallible Bible?” For, the majority of Christendom maintains a different canon than the Protestants: the Catholics possess 7 more books, the Eastern Orthodox maintain normally 9 more books, and some in the Non-Chalcedonian communion have canonized a whopping 81 total books. Therefore, the epistemological argument employed to validate the canon by Protestants can be utilized to defend the legitimacy of Tradition as well: the correct Church, Tradition, has been recognized by God’s people as divinely inspired, as well as doctrinally and logically coherent, and thus has merited the epistemological trust of the covenant people – especially by virtue of it preceding, producing, and preserving Scripture itself. To divorce Scripture from its Mother Church and Tradition is to completely nullify its efficacy, as Scripture is itself a part of the whole of Tradition.

• Misconception #5 •

“Catholics believe the Pope is infallible in everything he does and teaches.”

In Brief: As both the Eastern Orthodox and the Catholics believe Christ established one singular Church fully imbued with the Spirit of Truth, this Church will be led into all truth by the Spirit and cannot teach systemic heresy. As a result, heretics have always been viewed as outside the bounds of the Church due to their teaching of falsehood indicating that they have abandoned the Spirit of Truth which dwells within Christ’s Body. While councils composed of the world’s bishops are the fullest picture of the universal working of the Spirit, by pragmatic necessity and divine ordination of Peter to the primacy among the apostles, a particular bishop must be invested with the authority to make an infallible, final decision. As Christ granted Peter the new keys to the new kingdom, designating him as the new steward of the kingdom of the Church with universal authority, the bishop that takes up Peter’s mantle also functions as that infallible primate among the college of bishops. With Peter having died in Rome, Catholicism has dogmatized that the bishop of Rome, colloquially known as the “Pope,” maintains this infallible charism when inspired by the Spirit in Peter’s office to make a final, universal decision regarding the definition of a doctrinal truth.

Full Response: Aspects surrounding the theology of the papacy are unique to the communion of the Catholic Church and represent points of divergence from not only Protestantism but from Eastern Orthodoxy as well. Many misconceptions inundate this subject, as it remains an office without a strong parallel in other Christian systems. In contrast to Protestantism, the Catholic Church and Orthodox Church both hold that Christ established a particular Church to infallibly preserve the truth of the faith through the end of the age. The theological principle undergirding this proposition is foundationally that the Church is a sacramental participation in the divine-human hypostasis of Christ, and accordingly whichever Church maintains a complete participation in this theanthropic Body is guided by the Body’s Spirit, the Spirit of Truth, into all truth as promised by Christ. The Church is in fact the Body of Christ in a true sense, and as the human nature of Christ is deified by union with his divine nature, so too is the human element of the Church deified by union with Christ’s divine nature, preventing the one, true Church from falling into systemic error. The Holy Spirit imbues this literal Body of Christ on earth, guiding it in the deciphering of orthodoxy as Christ promised his disciples; thus, all heretical positions are immediate indications of a falling away from the Body of Christ and from his Spirit of Truth. Both the Catholic and Orthodox affirm this reality, and consequently believe that through Christ’s delegation of the authority to bind and loose to his apostles, the Church’s bishops inherit this prerogative to bind and loose on the laity the laws and doctrines of Christ’s kingdom. Accordingly, the normative operation of universally defining dogmas has been the convocation of councils consisting of the world’s bishops in order to arrive at an ecumenical decision on theological disputes. This practice finds precedent in the Council of Jerusalem recorded in the book of Acts in which all the apostles, who together possessed universal jurisdiction over the entire world, gathered to bind and loose a decision regarding the necessity of circumcision. While the first millennium of the Church strongly emphasized the importance of conciliar unanimity to demonstrate the guidance of the Holy Spirit, Catholicism concurrently underscored the necessity of a primate among the council to make a final, binding decision amidst any disputes that could not be unanimously resolved. If the proposition is granted that a particular Church will be guided into all truth until the end of age, then the Catholic Church discerned intrinsic to this Church must be a primate who is infallible when exercising his final, universally binding authority. The Catholic Church views Christ’s unique designation of Peter as the “Rock” upon which the Church is built – a Church which is divinely promised to never fall to the gates of Hades – and Christ’s delegation of the keys of the kingdom of heaven to Peter as indications that Peter was indeed to maintain this unique role of primate within Christ’s kingdom. As context, the keys were granted to the steward of the old kingdom of Israel when the king himself was no longer present and bestowed on this steward the very authority of the king himself. Thus, it is clear that Peter is receiving the unique authority of a steward over Christ’s new kingdom – the Church. The Catholic Church sees in Peter’s decisive, dogmatic declarations at the Council of Jerusalem evidence for his unique responsibility and prerogative to serve as a final, universal authority even among the apostles themselves. Both by pragmatic necessity and divine ordination, this primate is considered intrinsic to the very essence of the Church, and subsequently must continue in a successor to Peter’s office. As Peter demonstratively died in Rome, the bishop of this location took up his mantle of universal primate and has functioned accordingly to the present day: the office colloquially known as “Pope,” specifically the bishop of Rome. As a result, the Catholic Church holds not that the Pope is infallible in every statement he presents or document he composes, but only when universally, formally binding the Church to a doctrinal truth by virtue of his office as the successor to the divinely ordained primate Peter.

• Misconception #6 •

“The Cathodox worship Mary and the Saints.”

In Brief: The Cathodox paradigm regards salvation, not as a notional declaration of righteousness by God, but as literal participation in Christ as body to a head. Thus, to the degree that an individual enters into this union on earth, so will the individual participate in the works of Christ for all eternity. Therefore, as the Trinity shares in one activity among its diverse Persons, and as a Head executes all works through its Body, so too do those united to Christ’s Body share in his one activity. As certain acts are more characteristic of a Person of the Trinity or to a specific member of the body, despite all originating from the Father or head respectively, likewise so are certain acts attributed to certain Saints as they take on that character of the Saint despite ultimately originating in Christ. The fullness of attribution being accorded to Mary, as the immaculate New Ark of the Covenant who uniquely fully participates in Christ’s activity due to her spotless nature.

Full Response: Perhaps the most striking and scandalizing difference between Protestantism and Cathodoxy is the latter’s reverence towards Mary, the Saints, and the temporal hierarchy. I remain of the opinion that the lack of a Eucharistic-centric worship service results in Protestantism only being able to produce an exceedingly nebulous definition of “worship,” while the Cathodox are able to pinpoint “worship” specifically as the offering of a sacrifice to another being. Consequently, Protestantism’s understanding of that which constitutes “worship due to God alone” has culturally grown to include congregational music sung, prayerful petitions offered, or even strong acts of reverence towards another being (e.g. kissing and bowing). The Protestant definition is unfortunately not a coherent principle, but rather a conglomerate of various cultural impulses and apprehensions. For, music has always been sung corporately to other humans throughout history, whether during the modern day “Happy Birthday” ritual or in processions of royalty – no one would consider these as idolatrous but rather as displays of reverence. Likewise, a king’s ring has been kissed, servants have bowed to royalty, pictures of spouses have been affectionately venerated (kissed), and Christians have always petitioned fellow believers for prayer and assistance instead of singularly “going straight to God.” The wide gulf Protestantism has created between heaven and earth contributes to their hesitation in applying to the spiritual sphere that which is considered perfectly acceptable in the natural sphere, resulting in a “worship” service and devotional life radically disconnected from the human condition. The Cathodox, conversely, are capable of logical consistency in their application of these reverent practices to other humans while remaining worshipful of God alone, as the Eucharistic sacrifice is only offered to the Divine. In fact, in antiquity the Cathodox even condemned heretics who attempted to offer the Eucharist to Mary, as this adoration has always been reserved singularly for God.

Having established the logical validity of the Cathodox distinctions, a rationale should still be provided concerning the impetus for revering Mary and the Saints in the first place. The foundation of all theology is the Trinitarian life, as the entirety of reality has taken on the shape of its creator, and consequently an understanding of the relations between the Divine Persons is integral to grasping the dynamics of all other theological concepts, particularly Mary and the Saints. In brief, the Trinity is three distinct Persons who yet share numerically one essence. As the Church divined that the will and activity are faculties of the essence, the three Persons all thus share one single will and activity stemming from their single essence. Accordingly, when one of the Persons performs an action, all three of the Persons are in fact simultaneously performing that same action – not in the sense that distinct humans can join together to accomplish an activity in unison but rather the activity is performed in the manner of a single entity. However, it is normative in our verbiage to appropriate specific Trinitarian actions to a particular Person, as certain activities more intimately resemble the characteristics of one of the Persons. For example, theologians linguistically attribute the activity of sanctification to the Holy Spirit as the action appears more characteristic of his Person, yet in reality all of the Persons are performing that singular act of sanctification simultaneously. With this concept of divine unity as context, before his crucifixion Christ prayed to the Father that his followers might all be one as he and the Father are one. While the multiplicity of human essence prevents a unity directly equivalent to that of the Trinity, Christ is indeed calling his people to a union that approaches that level of communion, analogous to that of a head and a body. The further one grows in this unity with Christ, the more intensely his own will and activity become one with Christ’s, just as the activities of the body are also principal acts of the head as they find their origin within the mind. The Saints are then those who have entered into this eternal communion with God and consequently when Christ, the head, performs an activity, those joined to him, as his body, likewise participate in the activity’s execution. Christ is of course the source and summit of the activity, as the head is the origin of all human activities, nevertheless those united to him are instrumental causes of the action in the same respect that the body’s members execute the mind’s directions. In fact, like the appropriation of certain Trinitarian activities to particular Divine Persons, so too are various bodily actions more properly ascribed to a specific member despite all originating in the mind of the head: walking to the legs, throwing to the arms, eating to the mouth, etc. Accordingly, as the Saints conjoined to Christ are called to resemble Trinitarian union and subsist analogously to his Body, certain activities originating in Christ can be appropriated to specific Saints when those activities of the whole Body are more characteristic of particular Saints. This explains the Cathodox practice of petitioning individual Saints for specific areas of assistance (i.e. requesting St. Athanasius help a Christian grow in his understanding of the nature of Christ), as ultimately the spiritual assistance would be principally accomplished by Christ as the head but would be executed through the Body, resulting in this activity being most characteristic of, and appropriated to, a particular Saint. As a result, the Cathodox petitioning of Saints based on their various characteristics for spiritual assistance in corresponding fields of reality does not undercut Christ as the head and source of all spiritual assistance, but rather reflects the Trinitarian union in activity and fulfills the biblical mandate for Christians to become Christ’s Body. As the new immaculate Ark of the Covenant, Mary herself serves as the pinnacle participant in this union with Christ due to her uniquely spotless nature. This results in the activities of Christ being fully executed through her, as an unblemished participant in him, with Mary’s role paralleling that of the Moon’s relation to the Sun. From humanity’s perspective, the Moon appears equivalent in size to the Sun, but in reality subsists infinitesimally smaller while merely reflecting – as opposed to originating – the Sun’s light. It is this light of the eternal Son imbuing the Saints, and reaching its apex in Mary, that merits reverence from all Christians. These rays of light unite the celestial bodies in one act of illumination of the earth, as the Saints joined to Christ spiritually enlighten the souls of our world. In the end, the Cathodox paradigm maintains worship of the Triune God alone through offering only him the Eucharistic sacrifice, while communing with the Saints infused within Christ’s Body as an image of the eternal union of Triune love.

*A Note on Mariology: Perhaps the most scandalous of all Cathodox theology is the high reverence afforded to Mary, as in the Protestant mind: 1) the honor appears to rival that due solely to God and 2) the rationale for Mary’s importance remains radically unclear. Hopefully, the prior responses have already provided some level of elucidation, but a note expounding on the subject would likely be beneficial. Firstly, it must be emphasized that worship in the modern and fullest sense is offered to God alone, as he remains the sole divine being in existence and therefore singularly merits the sacrifice of the Eucharist. However, where the Cathodox depart from the Protestants is principally in the Protestant notion that the centrality of Christ’s redemptive offering lies in his perfect keeping of the commandments. For, in the Cathodox paradigm, if Christ were to never sin but not be divine, he still would not affect man’s salvation, as man’s redemption requires the deification of his nature and accordingly the divine nature to be united to the human nature. Therefore, only the God-man could achieve this unification and deification of mankind – not any mere human even if they were to live an entire life free of sin. In fact, Mary was indeed such a person who through the grace of God refrained from violating a single commandment, yet her purely human nature was incapable of hypostatically uniting our nature to the divine – since she herself remained simply human. Mankind’s communion with the divine requires a Divine Person to bridge this soteriological gap, and thus only the incarnated Second Person of the Trinity could secure such a redemptive miracle. With this as context, just as the Old Testament’s Ark of the Covenant had to be made of wood considered incorruptible in order to house both the Spirit of God and the Word of God (the Law), likewise must the New Testament’s fulfillment of this Ark of the Covenant be created incorruptible in order to allow the Spirit of God to enter her fully and conceive within her the Word of God (Christ). No other human in history has been granted this grand of a responsibility and as a result no other human has been gifted such graces as Mary to be made fit for such a privilege. Thus, due to her intrinsically unique mission, God has made her singularly fit in the scheme of salvation to fulfill her role as the New Ark and House of God. The biblical writers were well aware of this reality, as her route to visit her cousin Elizabeth after the conception of Christ within her is the exact same route that the Ark of the Covenant took in its return to David. Indeed, when Mary enters the house of Elizabeth, John the Baptist, like David, leaps for joy in his mother’s womb and Elizabeth echoes the words of David at this parallel moment when she proclaims, “who am I that the Mother of my Lord should enter my house!” Moreover, in his book of Revelation, the Apostle John parallels the Ark of the Covenant seen in Heaven with a Woman of Glory who gives birth to the Savior of the World – undoubtedly, drawing an equivalence in archetypes that his Jewish readers would have readily recognized. As the New Ark, the uncorrupted nature that Mary was gifted at her conception purely by the grace of God based on the foreseen work of Christ elevated her to the ontological status of Eve, so that there would fittingly be a new Eve alongside the new Adam. As a result of her immaculate nature, she was able to fully participate in the supernatural union with Christ and consequently subsists as the highest among the Saints in the Body’s participation of the Head’s works. Therefore, as we walk in the dark night of this world, the Moon fully illuminates our path towards the heavens by reflecting the rays of her Sun without diminution.

• Misconception #7 •

“The Cathodox worship icons and statues.”

In Brief: Just as any individual may display acts of affection to pictures of loved ones, so too do the Cathodox simply revere Saints through depictions in icons and statues. It is in reality that simple. No Cathodox claims to worship the actual icon or statue, but solely utilizes them to recall the individual depicted to mind and accordingly kiss or bow out of reverence and affection. For, as the Son is the image of the Father and adoration is granted to the Father through the image of his Son, so is it fitting for his Church to maintain the same principle by honoring through images those united to Christ.

Full Response: Inexplicably, the innocuous practice of kissing, bowing to, or praying alongside images of Christ and his Saints has attracted intense levels of opposition for over a millennium. The devotion has been subjected to an onslaught of mischaracterizations from theological opponents, especially within the low-church Protestant sects. The simplest approach to understanding the veneration of images is quite basic: if you have ever placed a picture of a loved one on your night stand and kissed it out of affection for the person depicted in the image, you have indeed performed the exact same act as “icon veneration.” The Cathodox simply believe icons and statues merely represent the human being depicted, and they appropriately offer a sign of affection to the person symbolized in the image. Nobody in the Cathodox religion, unless radically misled or uninformed (and I have never met such a person), has ever considered the person depicted as literally existing within the picture and statue, nor have they sought to literally worship the depiction itself. Perhaps, the reader may be concerned that the Ten Commandments dictate that no graven images should be created; however, it is imperative to note that God subsequently commanded the Israelites to fashion statues of angels on the Ark of the Covenant. The context of the commandment against graven images elucidates this supposed contradiction, in that God forbade the creation of graven images with the intent to worship them – not the creation of images in general. In fact, Scripture itself refers to Christ as the image of the Father, and accordingly his Body, the Church, emulates Christ in this regard by affirming the validity of pictorially depicting Christ and his Saints in order to offer them reverence just as honor is given to the Father through his own image in Christ. American Protestants, notably, practice their own type of “icon veneration” each time they ritually fold an American flag, as it is an icon of the nation itself and thus they attempt to venerate their country through the respectful treatment of its flag. Unfortunately, most opponents of icon veneration conflate the actual act of veneration itself with the distinct practice of prayer to Saints, since both acts regularly take place together. However, these are in fact separate categories and logically must be addressed individually. There is not much else to say, except to simply underscore that the Cathodox are not the superstitious idolaters they are routinely slandered as.

• Misconception #8 •

“The Cathodox are not allowed to pray directly to God but must go through a priest.”

In Brief: Since the New Covenant is a fulfillment, and not a total annihilation, of the Old Covenant it retains the same hierarchical structure – albeit while offering greater benefits. In fact, in the Old Covenant even an Israelite could pray directly to God; they simply relied on the priest to conduct sacrifices and liturgical life. Accordingly, the liturgical office of priest is maintained in the New Covenant and itself elevated to a sacrament, while offering to the recipient better promises: specifically, adoption into divine sonship through a sacramentally deifying mode of existence.

Full Response: The Cathodox office of “priest” remains widely misunderstood in the lower-church sects of Protestantism, as many maintain an erroneous notion even of its precedent in the Old Testament. A common assumption in Protestant circles is that the Israelites were required to go through a priest in order to commune with God in any respect under the Old Covenant and the Cathodox have retained this great chasm between man and his creator through their preservation of the priestly office. The result is that Protestantism often caricatures the Cathodox as only being able to experience God inside the Church building, being restricted to uniform prayers approved by priests, having to go through a priest in order to communicate with God in any capacity, and a host of other related misconceptions. In reality, while the priests under the Old Covenant retained certain prerogatives, the Israelites even then could commune directly with God as demonstrated through their daily and nightly prayers away from the temple. The Israelites principally relied on the priests for the administration of sacrifices and liturgy – an aspect that remains true within the New Covenant but with greater promises imparted to the laity and clergy alike. For, while the High Priest of Israel administered the blood of bulls and goats, the High Priest of the Church, the bishop, administers the life-giving blood of the New Covenant in Christ’s blood. Whereas, the Israelites were merely ritually covered in the earthly blood of animals, the Church communes with divine blood that transforms the recipients’ very nature. The veil was torn at Christ’s crucifixion, not to symbolize the cessation of all ritual and liturgical offices, but rather to symbolize that access is now granted into the heavenly Holy of Holies through Christ, as this divine-human reality now imbues the entirety of the new liturgical mass. The priests, similar to as in the Old Covenant, remain the primary facilitators of this new liturgical life, but offer a greater participation in divinity as the veil between heaven and earth has been torn. Consequently, the priest leaves the symbolic Holy of Holies in the Church’s sanctuary and brings to the laity residing in the nave the body and blood of the ascended Christ in order to participate in divine union. Thus, while the lay-people in Cathodoxy are in fact able to commune with God in their daily life through direct prayer, the pinnacle of the faith takes place within the liturgical mass administered through the new priests where Christ himself consummates his union with his people through literally entering into them and transforming the entirety of their very being. Furthermore, as the fulfillment, in contrast to utter annihilation, of the Old Covenant, the New Covenant likewise upholds its clergy as the administrators of God’s granting of forgiveness. In Protestantism, there subsists a strong apprehension at the idea of God working through another entity without diminishing his own power and glory. Of course upon reflection this is not consistently held even within Protestantism, as its adherents affirm that God works through the Scriptures in order to sanctify and save. Correspondingly, God can, and fittingly does, work through instrumental causes in order to accomplish his purposes, namely his priests in order to facilitate reconciliation within his covenants. For, as the priests of the Old Covenant accomplished reconciliation through animal sacrifices, so is forgiveness of sins imparted through the priests in the New Covenant based on the supernatural sacraments established by the Son of God. Christ indicated the reality of this authority when he told the apostles, “If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained” (John 20:23). Much interpretive gymnastics have been performed trying to avoid the obvious meaning of this verse: Christ established a particular office with the prerogative to forgive and retain sins. Some Protestants yield to this evident meaning, yet posit that the office ceased with the apostles; however, the Cathodox perspective understands Christ to have been establishing the essential constitution of his Church throughout his ministry and thus to have created an office with such vital authority that ceased merely after one generation would be entirely unfitting and arbitrary, to say the least. Accordingly, just as the keys to enter the Old Covenant kingdom were given to the steward once the king had departed, so are the new keys with the same authority granted to the apostolic office of the new clergy to determine who may enter and re-enter into Christ’s new kingdom through the forgiving or retaining of mortal sins which bar one from Eucharistic communion.

• Misconception #9 •

“Christ is re-sacrificed in every Cathodox mass.”

In Brief: The Cathodox believe not that Christ is sacrificed anew each mass, but rather that the original sacrifice is made present once again at the mass – analogous to time travel. This is necessary so that participation in Christ’s one salvific offering may be available to all people throughout all time. The liturgical sacrifice itself takes on the full range of human nature, in its physicality and spirituality, and thus transubstantiation is the only possibility of Christ consummating and elevating the entirety of his physical and spiritual Church into a deified mode of existence that is all-encompassing.

Full Response: While the Cathodox understand the original sacrifice of Christ to be made present in every liturgical mass, it is erroneous to claim they believe Christ to be sacrificed anew in each mass. Rather, the mass is analogous to an experience of time travel where the participants are communing with the one, original sacrifice – not a re-sacrifice of Christ. This accords with the principle underscored in Hebrews 10 that Christ was “sacrificed once for all,” which in fact denotes that he was sacrificed once for the benefit of all. In order for all to fully receive the benefit of this singular sacrifice, it must be made available for all to enter into and therefore it is re-instantiated at each mass for all to partake. However, if the sacrament were merely a spiritual or symbolic reality, then the participants’ experience of the crucifixion and correspondingly their union with Christ would likewise only be spiritual or symbolic instead of consuming the entirety of their being (making the physical resurrection itself superfluous, among other things). Rather, the entirety of Christ, his physicality and his spirituality, is made present in order that the recipients of the sacrament may be physically and spiritually deified – redeeming the whole of human nature. The Eucharist is therefore the consummation of the Bridegroom with his Bride, where Christ literally enters into his Church in order to become one with her and transform her into his image. Notably, on the natural plane of reality, the male’s DNA likewise enters the female and remains within her body for her entire earthly existence, conforming her into the image of the male to a degree indeed superseded by Christ and his Church. There are a myriad of angles to further approach this pinnacle subject, ranging from the fulfillment of the divine mandate to consume the Passover lamb to citations of Christ’s own words in John 6, but perhaps it suffices to underscore that as Christ took on the entirety of human nature, so too must we be united into the entirety of Christ in order to be saved – and only the Eucharist of transubstantiation provides man with the opportunity to enter into the totality of this consummative union with the Divine.

• Misconception #10 •

Note: A number of peripheral misconceptions sometimes maintained among Protestants will now be addressed more succinctly within Misconception #10 below.

• Misconception #10.1 •

“The Cathodox do not believe Christ resurrected, which is the reason for their use of crucifixes.”

Response: There are not many misconceptions more incorrect than this one, as the resurrection, like in all Christian faiths, is central to the Cathodox paradigm. Depictions of the crucified Christ are maintained, not because his subsequent resurrection is not accepted, but simply due to the fact that the crucifix is a real article of the faith that is honored – just like creation, the Passover, the giving of the Law – even if superseded by a successive event. It really is that simple. The crucifix’s association with exorcisms, nonetheless, derives from Christ’s crucifixion being a fulfillment of the statue of the bronze serpent hung on a stake which healed the Israelites from venomous snakes, as Christ being hung on the stake of a cross heals his Church from the venomous serpent of Satan and is fittingly used in exorcisms as a result.

• Misconception #10.2 •

“Cathodox hold that the sacraments are effective simply by virtue of the form while the consent of the recipient is not required. Thus, for example, if one is baptized against his will, it remains efficacious.”

Response: This conception is erroneous as the Cathodox uphold that the individual must consent and maintain sincerity in his participation with the sacraments, for the sacraments are not a wooden method of transactional deification. Rather, they parallel the Protestant understanding of Scripture through which God can provide sanctifying grace if the reader is properly disposed for its reception – not that the reader grows in sanctity just by virtue of mindlessly reading the words on the page. Accordingly, the sacrament of confession or of the Eucharist heals and deifies a participant’s soul to the extent that he disposes himself to sincerely synergize with the graces offered therein. Likewise, an individual being baptized must consent to the action in order for the sacrament to be of effect, and one cannot dump water on a random passerby in order to declare them sacramentally baptized. In the case of an infant, the consent of the parents is recognized as sufficient for the validity of the sacrament, for just as a child does not actively consent to his natural conception, neither is it necessary for the child to consent to his spiritual conception. As Colossians 2:11-12 indicates, baptism is the New Covenant’s initiation ritual paralleling that of circumcision in the Old Covenant and thus neither initiation ritual requires the active consent of the infant for validity.

• Misconception #10.3 •

“The Catholic Church historically endorsed that heaven could be purchased.”

Response: Without extensively devolving into the principles behind indulgences and penance, it suffices to state that the Catholic Church has never magisterially endorsed abuses related to meriting heaven through financial contributions. The Catholic Church is often characterized as having maintained that an individual could pay the Church enough money in order to enter heaven. This has never been the Catholic position, rather the Church has always simply held that an individual could fulfill his prescribed penance through almsgiving. Unfortunately, this legitimate practice was co-opted by corrupt individuals in order to nefariously raise funds for the construction of a new basilica in exchange for the reduction of post-mortem penance. This perversion of almsgiving never received magisterial sanction. As a note, the Eastern Orthodox themselves never maintained a practice similar to indulgences in any widespread or official respect.

• Misconception #10.4 •

“Catholics believe that the Pope is infallible when sitting in the literal Chair of Peter.”

Response: Among Protestant laity and even theologians, I have encountered a colossal, but perhaps understandable, misconception: that the Pope must be sitting in Peter’s literal chair in order to be functioning infallibly. Such an idea is obviously asinine and it is no wonder Catholicism is mocked when assumptions such as this are held. In reality, “chair” is merely a theological term for “office,” and all that is meant by the Pope being in the “chair of Peter” is that he is functioning in Peter’s office established by Christ. Thus, the Pope is only infallible when exercising a final judgment on a doctrinal matter over the whole Church, a prerogative unique to Peter – not when sitting in a literal chair.

• Misconception #10.5 •

“Catholicism historically dictated that the Bible could not be translated into the vernacular.”

Response: Many heroic lores have been propagandized by Protestants in order to foster the narrative that Catholicism has historically been a satanic persecutor of God’s true believers. The typical narrative is something along the lines of “so and so rose up and demanded that the average citizen should have access to the Bible so that they can read it for themselves and finally understand that the Catholic Church has been lying to the people about the Scriptures!” In reality: 1) the Bible was in Latin because this was in fact the vernacular in the West for centuries 2) the Church indeed promoted translations of the Bible in English and various other vernaculars but suppressed some translations, like Tyndale’s, because they were simply poorly done. In Tyndale’s particular case, for example, his translation was deficient as he twisted the original text to accommodate his heresies. Thus, the Church never condemned individuals solely for translating the Scripture but due to the promotion of heresy. Indeed, John Wycliffe is paraded as a forerunner to Luther in that he supposedly tried to free the common man from the yoke of the Catholic Church through the translation of Scripture, but in reality the Church held a council in 1414 that listed and condemned his various heresies – none of which entailed translating Scripture into the vernacular. It is significant that these mythic “Luther forerunners” never agree with each other, nor with modern Protestants, in their overall theology, instead they only agree on one topic across the board: disdain for Rome. Unfortunately, this is truly all Protestantism remains in substance, an anti-religion.

A superior mind would have undoubtedly explicated more fittingly and comprehensively the abundant truths of God, but “if they were all written down, I suppose the whole world could not contain the books that would be written.” In spite of my inadequacy, I hope this has served to elucidate the Cathodox perspective and disposed the hearts of all those who seek the Truth towards the movement of his Holy Spirit which reposes within the sacramental Body of his one Church for all eternity.

†

St. Peter, help us.

Leave a reply to The Fiat of Conversion – Tribe of Benjamin Cancel reply